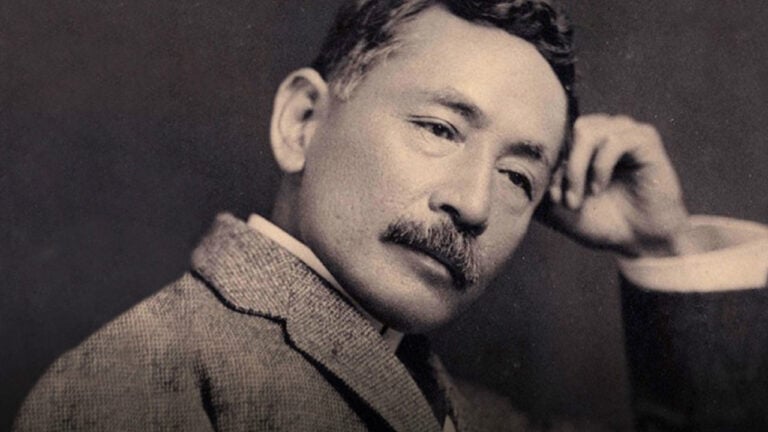

Haruki Murakami is in my mind the foremost name one associates with contemporary Japanese literature. However, given the right person and the right purview for what constitutes “contemporary,” one may easily say Natsume Soseki instead. There is a very short list of authors that any reader even mildly appraised to Asian fiction will know, and Natsume Soseki is one of them.

The source of his notoriety is better read than merely told about. That is to say, if you haven’t read anything by him, start with his 1914 novel Kokoro. It’s a truly touching story that ends in tragedy—intended, I reckon, to open up discussion about its cause (and indeed the book has been widely debated). The vulnerability of his characters and the tastefulness with which he glides into difficult subject matter is unparalleled. Kokoro sees its namesake—the heart—viewed through the minimized, abstracted view that the Japanese mind seems perfectly ready to conjure up at the stroke of a pen. Botchan and the satirical I am a Cat also deserve a read.

Childhood and Education

For every bit of prowess demonstrated in Soseki’s work, there has always been an underlying trauma in his real life. He’s a bit like Lovecraft in a way, not in style but in the life of the man—an unwanted genius flourishing in squalid conditions—although receiving more notoriety than the former in his day.

Soseki was born in Edo (now Tokyo) as an unwanted child, to parents too young and tired to possess the vigor that parenting demands. Though they were well off, the presence of a toddler among his much older siblings was so much a disgrace to his family that they offered Soseki up for adoption. His adoptive parents divorced when he was nine years old. He grew up studying Chinese classics and various Asian fiction and as a young man developed an affinity for English. Despite disapproval from those around him and initial plans to become an architect, he found encouragement from the great poet Masaoka Shiki, who ultimately made up Soseki’s mind on what he wanted to do with his career.

England Stay

In 1900, he was sent to England by the Japanese government to act as an ambassador for his nation’s literary scholarship. While initially applying for Cambridge, the expensive tuition led him instead to University College London. After two years he returned to Japan, dejected by the experience and with nothing of positive note to say about the endeavor. Yet, I think this experience certainly boosted his already encyclopedic knowledge of literature, because for a time in London he had done nothing but hole himself in his lodgings and read.

Yes, Natsume Soseki was an expat himself, as many of you reading are. Were Soseki alive today, he would be described as a Hikikomori. A shut-in, he lived in the damp choking air of his cheap apartment for years with little human interaction, doggedly focused on his study of the English and their talon-like grasp of prose. Breathing in the moldy air of a cramped, musty apartment 24/7 probably would’ve driven anyone insane with culture shock, but Soseki was introverted to his own benefit, using this self-imposed house arrest to conjure up some of the best literature in Japan’s history.

Well, the above is what’s is oft-repeated at least. While Soseki certainly felt some level of disappointment from the experience, it must be noted that while the stay was miserable for him, he was impressed with the English people. Writing in a letter, he noted:

“I am deeply impressed that people here are full of public spirit. If there is no seat on the t

rain and you are standing, even a lower-class laborer will make room for you. In Japan there are some simpletons who take great delight in occupying seats enough for two people.”

Why the seeming cognitive dissonance? Allow me to explain.

Culture Shock

Etsuko Nakayama, a Doctor of Literature from the University of Hawaii, penned an essay on Soseki’s sojourn to the west (Natsume Soseki in England: The Meaning of His Encounter with the West), which collated several sources to come to the conclusion that Soseki had gone through the classic stages of culture shock: Honeymoon, Hostility, Humor and Home. That is to say, at first Soseki was in his Honeymoon phase, in wonderment at the exhilaration of the new. Once he had entered the second stage, the contentment of familiarity had set in as he struggled to make meaningful social connections in this new environment. That second stage, Hostility, if stayed in too long, can cause a mental breakdown and even psychosis, which explains Soseki’s relief to return to his home after the two-year stay. This also puts into context why the majority of his letters were bitter and negative, despite Soseki’s appraisal of the English being all-in-all positive.

Nakayama goes on to elaborate that the factors leading to this prolonged hostility to a different culture have been explained by psychiatrist Hiroshi Kondo: Natural Environment and Social Environment, the latter encompassing Human Environmental Factors, Psychological Environmental Factors, and Material Environment Factors. For Soseki, this translated into hating the climate and smog of London, being separated from his family, his feeling of inferiority to the English, and perhaps foremost his lack of money, respectively.

Reading this analysis as well as Soseki’s letters, I couldn’t help but recognize his feelings. It was as if I was reading about my own experiences in Japan when I had just arrived. I too had stayed for too long in the hostility phase, and for largely the same reasons that he did. Soseki spoke of his time in London very little publicly and I think he may have missed an opportunity to advise (or perhaps warn) others of what to expect from a similar experience. Soseki, ever Japanese, deemed his extraordinary and admirable endeavor into a different culture as a failure.

Like the characters in his novel Kokoro, he kept his guilt close to the vest. I would’ve loved to read more of his experiences in detail (perhaps in the semi-true-to-life George Orwell’s Down and Out method), but if nothing else, we can find comfort in the fact that even a great artist such as himself, with even the endorsement and subsidy of the Japanese government, experienced many of the same issues that you reading this article have in Japan as well, right now.

Final Thoughts

Books have been filled with analysis of this man’s work that I’m unable to reproduce. All I wish to do in this article is pique your interest to an often unexplored aspect of a famous author’s life. If you’re not the reading type, his life has been represented in many forms of media, spanning dramas, anime and even video games—with some depictions more of a caricature than others.

I own a copy of Kokoro, but with some embarrassment I confess that I’ve never read it in its native language. Literature of this age proves challenging even with one’s native language, and though I try, I’m not yet at the level where I can understand Soseki’s work on the face of it, let alone in the many nuances that only those fluent in a language will even have the chance of detecting (if you don’t believe me, try to translate James Joyce into Japanese to a native speaker—“love loves to love love” is always good for a laugh). Japanese literature is put through a similar hurdle in translation.

Yet, while I have only the approximation of Soseki’s vision that a translated copy brings to the discussion, I can say with confidence that his work is nigh infallible, even given the limitations a translation inherently possesses. The Bank of Japan seems to agree, as they put his face on the 1,000 yen bill between 1984 and 2004. Coming from a country that only puts political leaders on money, it’s refreshing to see the spotlight given to an artist like this, even posthumously. If you don’t want that iconography to go to waste, you owe it to yourself to study more about the man and read some of his work.