In March 2014, the former Prime Minister of Japan, Shinzo Abe, created a council for the promotion of female employment. Before that, in April 2013, his government had already passed a “Declaration of Action for a Society where Women Shine” and launched what was called the “Womenomics”. This program aimed to have 30% of women occupy positions of responsibility by 2020. However, on March 31, 2021, the World Economic Forum released its Global Gender Gap Report. Among the 156 countries that were analyzed, Japan was ranked 120, one position above the December 2019 report, but still far at the bottom of the rankings.

Employment vs Maternity

Even today, Japanese women seem to have to choose between employment and motherhood. In Japan, a woman who becomes a mother is unlikely to be promoted in the company as traditional company managers think that their mind is too focused on what happens at home.

The culture of long working hours, the traditional system of remuneration and promotion based on the worker’s seniority, the difficulty in accessing daycare centers in large cities and the lack of opportunities for women to resume their jobs after their maternity leave are just some of the obstacles that Japanese women must overcome if they want to pursue their professional careers.

Pressure and harassment at work towards working women who wish to have children is so common that there is a specific term for it: “matahara” (マタハラ). The results of a survey carried out by the Rengo trade union confederation on work and pregnancy in early 2015 indicated that one in five women had suffered some type of harassment in their workplace when they became pregnant. Among the 1,000 women who responded to the survey, 21% said they had received unfavorable treatment, while 10% said they had suffered verbal harassment. 8% commented that they were either fired or their contracts were not renewed when they became pregnant.

Precarious Jobs

According to a study by the International Labor Organization published in 2019, in 2018 only 12% of the female workforce in Japan entered the labor market, compared to the world average of 27.1%. While it is true that women have been entering more the Japanese labor market in recent years, analysts believe that this has been due more to the lack of labor and the crisis of workers that the country is going through because of the aging of the population than to a structural change in its idiosyncrasy.

One of the main problems is that a significant percentage of this female work is actually considered “junk jobs”. It is estimated that a third of female workers do part-time and close to the same percentage are considered to be overqualified for the position they hold.

Abuse and Harassment at Work

Socially, the Japanese collective imaginary continues to objectify women quite openly. This is the case of being touched in the train. In order to prevent these abuses, some train cars are often reserved exclusively for women during rush hour. Likewise, a representative and media case about the harassment of women was that of the idol musical group NGT48 in 2018. One of its now former members, Maho Yamaguchi, had to publicly apologize for “causing disturbances” among his followers after having narrated in Internet how she was assaulted by two men in her own home.

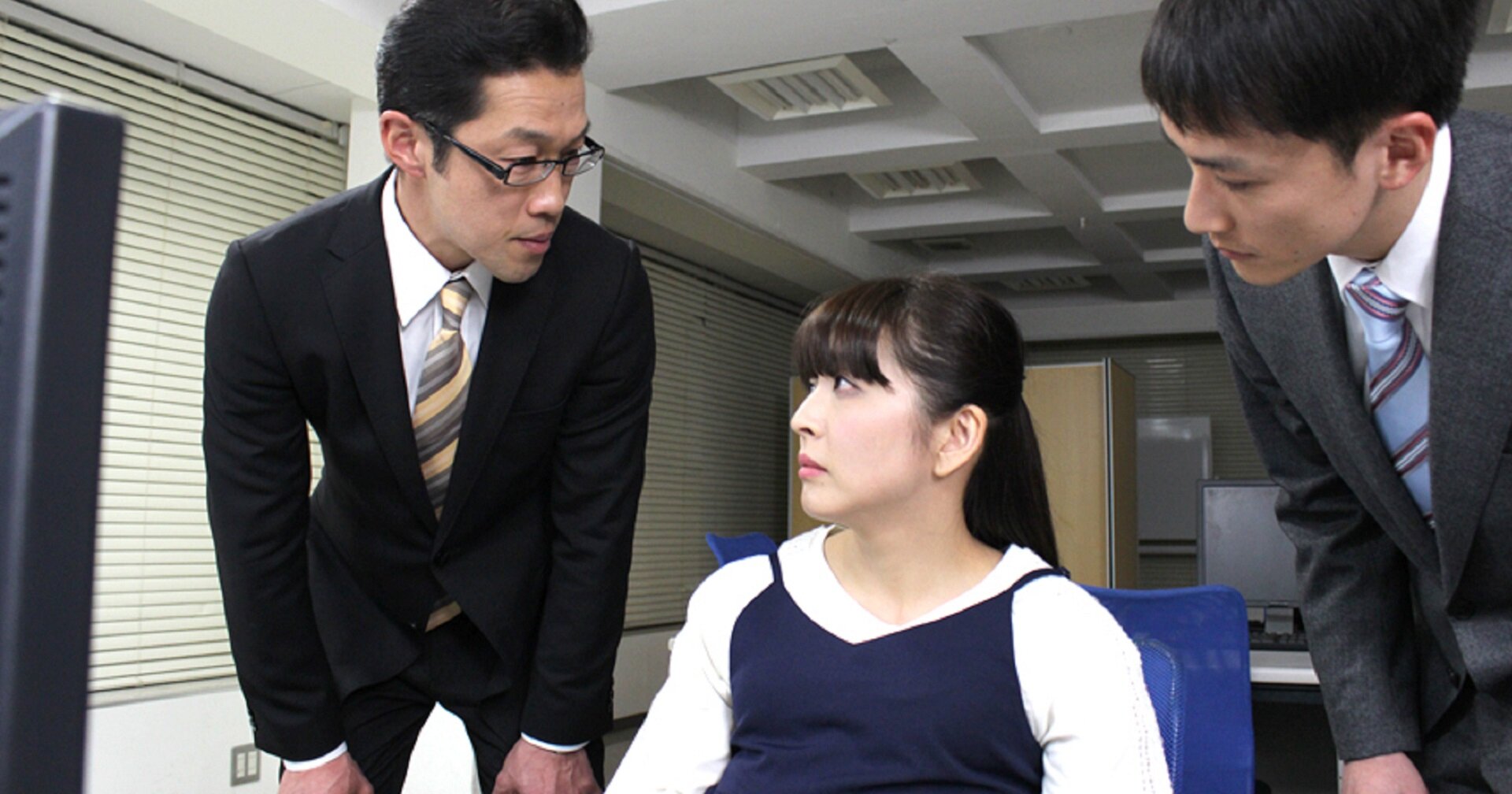

Within the labor market in Japan, another serious problem for women is the treatment they receive from their colleagues and superiors. A 2016 government survey of more than 9,600 working women between the ages of 25 and 44 found that nearly a third of Japanese working women had been sexually harassed in their workplace.

As if this was not worrying enough, more than half confessed to having been the victims of comments about their appearance, age or physique, especially by male colleagues (and in 24.1% of cases by their boss). Likewise, 37% confessed to having had to put up with an excessive number of questions about their private life (especially regarding their marital status or children). In the most serious cases, a very high 40% confessed to having been the victim of inappropriate touching, 28% had been persistently asked to go out and date and 17% commented that they had been pressured to have sex.

Sexual abuse at work is so widespread in Japan that there is even a specific term to refer to it: “sekuhara” (セ ク ハ ラ), which comes from the abbreviation of the words “sex” and harassement”.

Lack of Political and Economic Representation

The Inter-Parliamentary Union assured that it is estimated that only one in ten jobs in high positions and in politics are held by women, the worst figure recorded of all the countries that make up the G20. Although there has been some improvements, serious difficulties persist for the incorporation of women in this field, and many of them suffer some type of abuse throughout their professional careers.

This is the case of the current governor of Tokyo, Yuriko Kokie, the first woman to hold this position. She is the founder of the Party of Hope and was a former fellow activist of former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. Kokie came to that position after winning the elections in June 2016. However, her campaign was full of obstacles from her co-workers, who even said of her that “on the inside she is a hard-line man”, since she was operated in 1998 of ovaries due to cystic fibrosis.

In 2014, deputy Ayaka Shiomura was insulted and booed by other deputies during her speech at a Tokyo metropolitan government assembly with phrases such as “hurry up and get married” or “can’t you have children?”. The case jumped to the international press, which harshly criticized the macho stance of Japanese politicians. In the end, one deputy from the Liberal Democratic Party, Akihiro Suzuki, publicly apologized.

Much more recently, in February 2021, Yoshiro Mori, former chairman of the organizing committee for the Tokyo Olympics and Paralympics, ended up resigning after declaring that women talk too much and tend to drag out meetings.

The current situation of women in Japan is still complicated in some respects compared to that of men. While it seems that Japanese society is changing little by little, there still seems to be a long way to go for gender equality in Japan.