It’s no secret that arcades have been on the decline in the west for decades, while Japan is still the stalwart purveyor of all things coin-op. The reasons why are still debated, but I’ve always felt that the main factor is simply that western arcades simply aren’t that fun. In America at least, arcades are a novelty to pass time while you wait for your pizza. A select few arcade chains such as Round 1 (notably a Japanese company) are destinations in and of themselves, but this is the exception, not the rule.

Given all that, perhaps the western fascination with Japanese arcades is explicable, as is the mania to vlog about them. After all, where else in the world can you play crane games that are even remotely fair? Japan has offered a very different kind of arcade from the rest of the world for decades. Despite the ups and downs of the industry—though covid and all—they are still profitable. Why exactly did this happen? How did it start? Will it continue? These are questions we will discuss in this short retrospective.

The Late 1970s

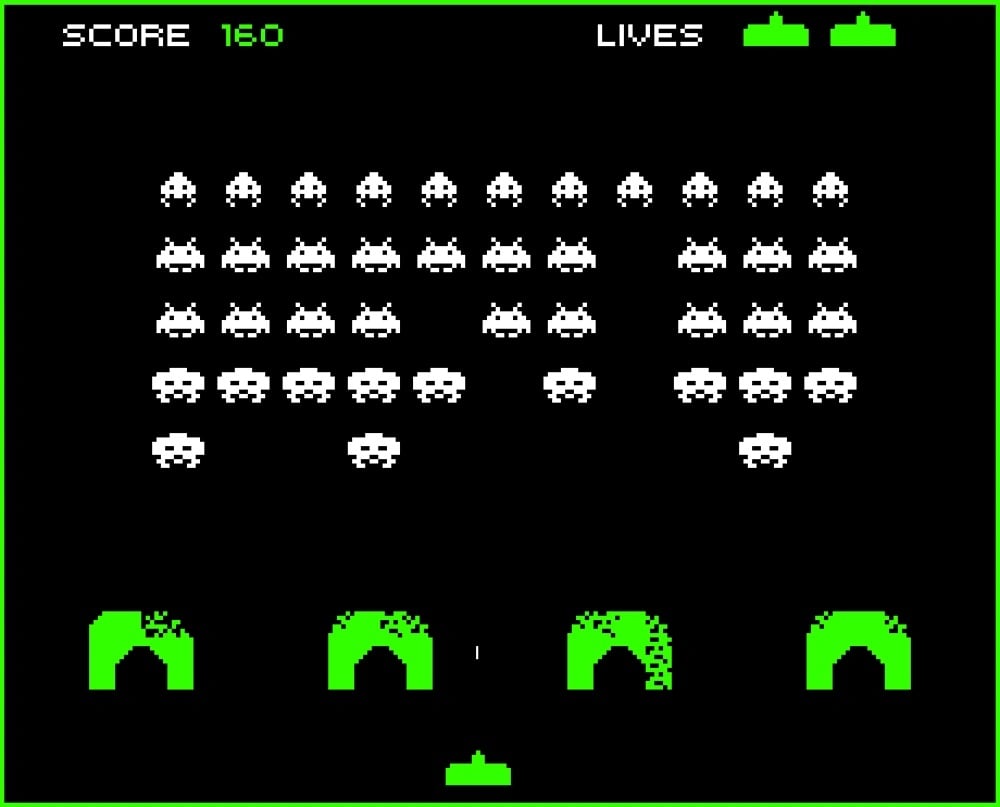

While senior outliers can be cherry-picked going back to the 50s, for all intents and purposes, video gaming started in the 70s. During this time we see the creation of the most crucial title regarding the rise of the Japanese arcade as we know it today: Space Invaders. The game was released by Taito in 1978. If you’ve ever wondered why the Taito brand adorns so many arcades in Japan, this would be the catalyst for why.

Space Invaders is dirt simple: You control a small doo-dad on the bottom-most portion of the screen, and aliens are descending from the top-most portion downwards. If they reach the player then it’s game over, so you have to shoot them all to win. The challenge comes courtesy of a limitation of processing power—eliminating aliens will allow the remaining ones to move faster, making the game more difficult as you get closer to victory.

This simple concept ensnared the imagination and money of the Japanese public to a degree yet unseen. The cost was one 100-yen coin per play, and not long after the game’s introduction there was a shortage of the 100-yen coin, causing circulation issues and emergency mintings. The 4-ton trucks used to transport bags of coins from arcades would sometimes compromise their suspension in attempts to haul the unprecedented gains.

A new era had begun.

The 1980s and 90s

![]()

With its work cut out for it, the new video game industry simply had to find out what would stick. As it turned out, there would be no true “next big thing,” but rather a tableau of now bonified classics like Pac-Man and Donkey Kong, which put Namco and Nintendo on the map respectively. Business was doing well, but by the end of the 80s, a paradigm shift was occurring.

The number of Japanese arcades peaked in 1986 at 26,573 locations, declining for almost every year after that. The reason why? The rise of the home console. Home game systems like the Famicom and PC Engine were snatching up arcade gamers, and in retrospect it’s not hard to see how: Why spend 100 yen per game when you can simply buy your own system and play as much as you want for free? It made sense to parents and kids alike. Soon, this new normal for playing games overtook arcades in terms of popularity.

This was, however, challenged in a big way for just a moment: The introduction of the fighting game. Capcom and SNK released a slew of wildly successful fighting games in the 90s, such as Street Fighter and Fatal Fury, which shifted the language of arcade game design away from single-player experiences like Space Invaders, and towards the more social experience of multiplayer, which fit public spaces such as arcades like a glove. Still, arcades continued to decline in presence throughout the 90s and even into the 2000s, despite early-millenium smash-hits like Dance Dance Revolution.

Arcades Today

While the number of arcades in Japan today has declined to around 2,000 locations, I feel that the relatively small number of arcades that remain have much enthusiasm behind them. You may ask: “How?” After all, the argument posed by gaming historians is that arcades failed because home consoles started offering something with more bang for your buck, and that fact has only become more and more true as the years go on. The Nintendo Switch, for example, is miles ahead of what any arcade machine can do on a technical level and has more games to boot, all for a lower price overall. Nowadays, video games only account for 12% of arcade revenue. For arcades to survive, they had to shift what demographic they were targeting. They had to move away from video games, and they did in a big way.

UFO catchers—games that use a mechanical claw to grab and win prizes—became the modern Space Invaders. Okay, that may be overselling it a bit, but believe me when I say that UFO catchers are the sole reason arcades thrive in Japan. UFO-catchers have real mechanical parts that move around to net you real, physical prizes—something that a game console is incapable of doing. In 2019, these crane games accounted for 55% of arcade revenue in Japan. That’s right, over half of the revenue from a modern arcade comes from trying to win a stuffed animal for your girlfriend.

With that in mind, it’s no wonder why crane games are always near the entrance of the arcade, while fighting and rhythm games (popular in their own right) are corralled somewhere near the back of the facility or on some tertiary floor. The age of arcades being a place to play video games is over. Now is the age of arcades as a general entertainment experience.

Arcades in the Future

For people who enjoy the old style of arcades, there will always be some way to experience that: Shout-outs to the Gamebox Q3 in Nagoya—an old-fashioned arcade that feels like traveling back in time to the early Heisei period. It’s dingy, grungy and full of character, filled with games that offer finger-numbing challenge. In short, it’s the kind of place that just doesn’t make money like it used to. During COVID-19, they had to run a GoFundMe to stay alive (thankfully, it worked).

There will one day be a time where the arcades of today will be old-fashioned and unprofitable. Despite that, I don’t think arcades will ever truly die out in Japan. They will certainly continue to decline in relevance, and for sure smartphones will march on in their quest consume people’s attention. Still, arcades will adapt to changing trends. At the end of the day, people just enjoy having something physical to interact with. Even if you were to develop an iPhone app that grabs prizes remotely and ships them to you (and people have tried to make that), it wouldn’t change the fact that the main draw of an arcade is the social aspect. As long as money and people exist, strangers will be willing to gawk at you while you waste 3,000 yen to win a giant chocolate bar from a Rube-Goldberg machine.

For an in-depth look Arcades in Japan, check out the documentary 100 yen.