Bullying in schools, resulting in the suffering of many children, remains a persistent problem worldwide. While bullying is not unique to any specific culture, Japan has experienced severe cases leading to the tragic deaths of children from primary school to high school.

“Ijime” (or bullying) involves the physical or psychological aggression directed towards someone perceived as weaker to a harmful degree. In 2019, the Japanese Ministry of Education reported increased school bullying, nearly 610,000 cases. Moreover, disturbing statistics reveal that suicide ranks among the leading causes of death among individuals aged 6 to 18, with up to 514 students below the age of 18 taking their lives in 2022.

While multiple factors contribute to issues like suicide, bullying remains significant in harming young individuals. In fact, there have been cases where bullying was identified as the direct cause. The most crucial aspect in addressing bullying is not to overlook subtle signs and respond appropriately.

However, while the problem is well known, more and more schools or educational administrations are not adequately handling cases of bullying. Even when evidence such as screenshots, photos, videos, and so on are clearly presented, many children find that those who are meant to protect them take no action or even try to conceal it.

In this article, I will discuss the issue of bullying (or ijime) in Japan. I will also explore how to identify signs that your child or student may be a victim of bullying and provide resources for addressing this issue.

The Problem at the Administrative Level

When we look at the administration, we see one of the first problems that occurs. It is not uncommon for bullying cases to go unidentified or outright ignored when reported.

For instance, in a tragic incident in 2012 in Otsu, Shiga Prefecture, a 13-year-old boy lost his life due to extreme bullying. Shockingly, his tormentors frequently coerced him into “practicing” taking his own life. While subsequent investigations revealed that over sixty students had witnessed the bullying, his teacher had dismissed these actions as mere jokes.

According to these accounts, three bullies physically assaulted the boy in the restroom, subjected him to the cruel act of consuming dead bees, and humiliated him by pulling down his pants and taping his mouth shut. Despite the school’s attempts to downplay bullying as a direct cause of the boy’s death and their efforts to conceal evidence, leaked information ignited public outrage over the case.

Another incident in 2016 resulted in the suicide of a junior high school student, with bullying, including name-calling and social exclusion, identified as the cause. Unfortunately, the student’s homeroom teacher failed to acknowledge the bullying and took no specific measures to address it, even though the student had expressed his distress in two school surveys, citing statements such as “Everyone says I’m disgusting” and “I’m being ignored.” The lack of intervention is suspected to have contributed to the student’s feelings of hopelessness.

In many instances, it has been claimed that the reports on such incidents mysteriously disappeared. The pertinent documents seem to vanish from the school or Education Board records. Such an explanation is deeply troubling and, at best, indicates gross negligence on the part of the administration in handling these cases.

Furthermore, even when neglect is exposed, rarely are those responsible held accountable or faced with severe consequences. In situations of severe bullying, when the parents of the bullied child request an investigation, the local administration is expected to take action, and an impartial third-party panel should conduct the inquiry.

However, this process is often bypassed, as administrators fear that it may reveal their inaction or cover-up. Instead, they opt to establish their own ‘Special Support Team,’ comprising government officials from the same municipality, undermining the transparency and impartiality of the investigation process.

Problem at the Teacher Level

A second problem occurs when looking at teachers themselves. Most teachers don’t outright want bullying to occur in their classrooms. In fact, most teachers probably do truly care about their students, but two issues arise when looking at teacher’s roles (or lack thereof) in bullying cases.

For one, similar to the administration, there are issues with the fact that once teachers acknowledge a bullying incident in their class, it can have significant repercussions for them. These include an increased workload, damage to their reputation, reduced compensation, and diminished prospects for career advancement. These factors often discourage teachers from acknowledging when bullying occurs.

However, another fact to consider is that teachers are often heavily overworked and under stress in Japan. A 2018 survey by the OECD revealed that Japanese junior high school teachers work approximately 56 hours per week, in contrast to the typical 38-hour work week common in most developed countries. Additionally, teachers in Japan accumulate an average of 123 overtime hours each week, significantly surpassing the acceptable limit of 80 hours.

Teachers are tasked with classroom instruction and are often involved in numerous extracurricular activities, such as after-school clubs, school events, parent-teacher associations (PTA), supplementary lessons, and student council responsibilities. This extensive workload has given rise to severe issues, including the health risks associated with overwork. During the 2015 school year, over 5,000 teachers took sick leave due to mental health concerns, and in a 10-year period spanning 2006 to 2016, 63 teachers succumbed to overwork-related causes.

Understandably, teachers may struggle to address bullying cases, even when brought to their attention. Neglect can easily occur when educators are overwhelmed and unable to function at their full capacity due to exhaustion and stress. While teachers may genuinely care for and love their students, they might inadvertently overlook challenging situations due to time constraints.

Addressing bullying can also significantly affect teachers’ mental well-being because of the emotional complexity of such situations. As Mariko Mashimo highlighted in her TEDxHimi presentation, “Teachers view both the bullies and the bullied as their students. They are reluctant to label students they care for as ‘the bully’ or ‘the bullied.’ Therefore, it’s unsurprising that teachers often attempt to address this issue by framing it as ‘interpersonal conflicts’ rather than ‘bullying,’ implying a power imbalance.”

It is also common to rephrase it differently, like ‘trouble with friends’ or ‘personal disagreements,’ and don’t want to admit that it was bullying at all. When questioned about the situation, it is common to point out, ‘But we need to care about the bullies’ future, right?’ It is common to fear that if bullying comes to light, the bully’s reputation will be slandered, affecting their future work opportunities, college placement, and public persona.

However, while it’s true that a child’s future shouldn’t be ruined because of something they did at 10 or 11 years old, it’s not doing the child any services by removing their opportunity to learn from their mistakes and reflect on their actions.

How is the Japanese school system structured?

To understand the reluctance to acknowledge power imbalances and take sides in cases of bullying, I think it’s important to understand the pressures of equality that exist within the Japanese school system. In 1990, Ichikawa outlined the distinctive characteristics of the Japanese education system. For example, some of these characteristics included the privatized development of pre-and post-compulsory education with a substantial share of private funding, a preference for general education under a single-track system, or unique screening functions of entrance exams.

The specific interest feature here is the remarkable combination of high educational achievement with minimal variation. International surveys evaluating math and science achievement, conducted by the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA), have revealed for many years now that Japanese students achieved exceptionally high scores among developed countries, with a remarkably small deviation in the results.

As previously shown, teachers in Japan are deeply committed to their work, including extracurricular activities, and they are supposed to treat all students impartially, avoiding favoritism towards gifted children. There are minimal disparities in learning conditions across different geographic areas. Factors such as school curricula, facilities, teacher qualifications, compensation, and public spending per student are nearly uniform nationwide.

Another noteworthy aspect is the homogeneity found in Japanese schools and classrooms. Unlike many other countries, where schools enroll diverse learners, including immigrant children, Japanese classrooms stand out for their exceptional homogeneity regarding cultural background and physical and mental development. The presence of non-Japanese students in Japanese schools and universities remains minimal, although I will return to this point later.

As you may have already noticed, this focus on equality can sometimes pressure teachers into maintaining a neutral stance when dealing with bullying despite the inherent power imbalance. The drive for equal treatment also tends to lead to the rejection of individuals who stand out within the structural level of the classroom.

The worst part is the bullied kids are abandoned and unable to rely on their teachers for protection, often forced to change to another school and experience immense trauma that affects their entire lives. There have been many cases where either or both the teachers and the administration don’t pay attention to the vulnerable kids who need their protection and help.

Problem at the Cultural Level

It’s easy to quickly point fingers at administrators and teachers and criticize their views, but it’s also important to acknowledge why the bullying occurs in the first place. It’s likely you’ve already heard people say that Japan is a ‘shame culture,’ but what does that mean?

Japanese society operates on a foundation of shame-driven thinking, where individuals refrain from immoral actions primarily because they would bring shame upon themselves. This goes beyond religious teachings, emphasizing how others perceive you, leading to the concept of ‘face’ (面).

I’ve explored this concept in greater detail in previous articles (“Japan Under Pressure: When Social Pressure Becomes Too Strong“), but in summary, ‘face’ is closely tied to your reputation and your interactions within the social sphere. Consequently, it’s vital to avoid behaviors that would bring shame to yourself and those connected to you, including friends, family, and colleagues.

This means that your public façade (or “tatemae”/建前) plays a significant role throughout your life. The pressure to uphold this facade places a heavy burden on both administrators and teachers in cases of bullying, but it also impacts the children involved.

Japan has a well-defined notion of what constitutes the ‘right kind of person,’ and there’s immense pressure to conform to this ideal path. While social pressure exists in all cultures, in Japan, where the societal facade and pressure are particularly strong, it’s understandable that children may emulate the behavior of adults in the classroom by excluding those perceived as different or divergent from the established norms.

It’s important to understand how potent the feeling of shame itself is. When coupled with teachers either being unresponsive to bullying, it’s no surprise that bullying takes root in the first place.

Shame is a tool often used in society to enforce conformity, pressuring both the individual causing the shame to avoid it by shaming others and the one experiencing shame to conform to societal norms to evade this feeling. However, according to an influential researcher in the psychology of shame named Brene Brown, “shame is the most powerful, master emotion. It’s the fear that we’re not good enough.”

Continuing the discussion on the homogeneity prevalent in Japanese schools and classrooms, as previously mentioned, the formal education system primarily caters to Japanese children, adolescents, and youths. In this context, we observe how the significant pressure to conform extends beyond systematic demands for standardization within the classroom, influencing students to compel one another to conform to the norm.

In addition to this, students themselves face considerable stress. The academic pressure is particularly intense. In Japan, many students dedicate long hours each day to studying, often participating in after-school clubs and attending cram schools. The university a student gets into holds great significance for their future, sometimes overshadowing their actual grades or degrees.

This heightened academic competition places additional strain on children. Bullies may exhibit irresponsible, impatience, self-centered, and flamboyant behaviors when feeling frustrated and inferior. Also, factors like bullies’ home life, pressures from their parents, struggles outside of school, and so on also contribute to their actions.

Consequently, children become targets of bullying for various reasons, whether due to their perceived intelligence, lack thereof, physical appearance, or simply for being different in some way.

How do I detect bullying in my student or child?

According to Ijime SOS (いじめSOS), an organization focused on helping raise awareness and address the problem of bullying in Japan, common forms of bullying include shunning or isolation, violence, destruction of victim’s property, and extortion (demand for money). These can range anywhere from name-calling and teasing to direct physical harm.

Statistics from the 2018 Indicators of School Crime and Safety report show that only 20% of school bullying incidents are reported. However, children often refrain from sharing their experiences with adults for many reasons.

Bullying can render a child feeling helpless, prompting them to attempt self-resolution in a bid to regain a sense of control. They might be apprehensive about appearing weak or like a tattletale, fearing potential retaliation from the bully. To make matters worse, bullying can be an intensely humiliating experience, discouraging children from disclosing what is said about them, whether true or false. The fear of judgment or punishment for being perceived as weak can also deter them from seeking help from adults.

So, it’s often vital to look for key signs of bullying. According to Ijimie SOS, the signs to look for are as follows:

- Dirty or damaged clothing

- Loss of personal belongings

- Reluctance to discuss school or friends

- Arriving home late

- Sudden increase in phone calls or emails

- Sudden requests for additional money, such as pocket money

Although looking at this list, it can be quite difficult to gauge bullying behavior. Kids getting clothes dirty while playing outside or losing things in the chaos of being a kid is quite normal. However, sudden changes in attitudes or behaviors are another important thing to notice. Often, victims of bullying will suffer changes in eating habits, declining interest in school, a decrease in self-esteem, self-destructive behaviors such as self-harm, and signs of depression and anxiety.

How do I handle bullying in Japan?

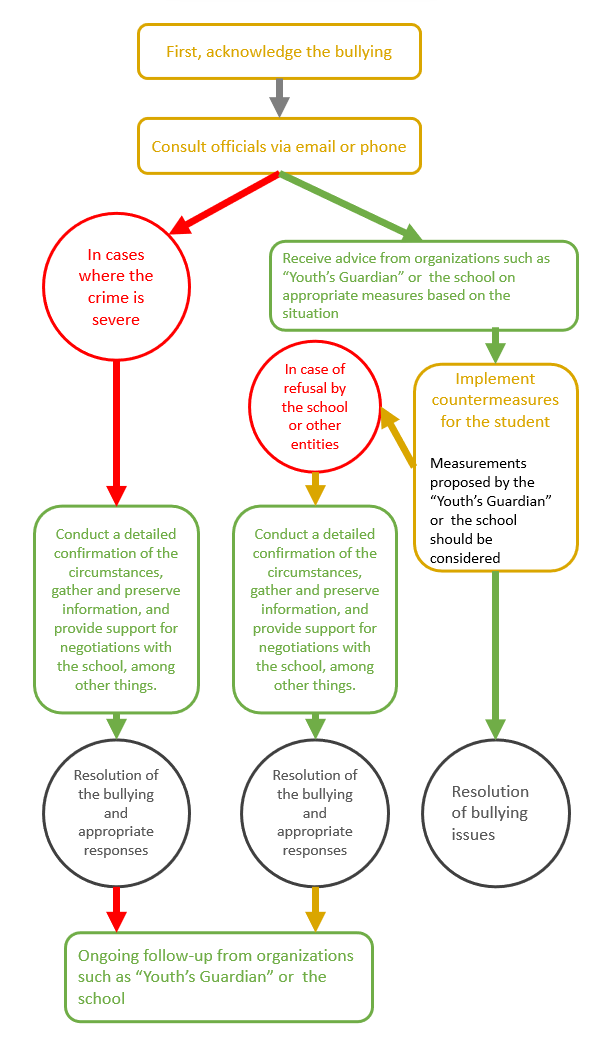

Now, perhaps you do find out that either your child or one of your students is being bullied. What do you do now? IjimeSOS provides a flow chart of how to handle bullying that you can find here [insert link: http://ijime-sos.com/hogosha/]; however, the English translation can be seen below.

Additionally, you can find various hotlines to handle bullying cases if your school is unresponsive to your case.

Another crucial aspect to bear in mind is consistently providing support to the victim. Ensure their physical safety, reassure them that they are not alone, and in severe cases, consider seeking assistance from a mental health practitioner to help the child cope with the traumatic experience.

Youtubers Discussing Bullying Experiences in Japan:

Why Bullying is So Common in Japan — The Japan Reporter

【相談】【いじめ】いじめられて不登校になった過去 — mayoの日常っ。

Bullying in Japanese Schools is NO Joke — Let’s ask Shogo | Your Japanese friend in Kyoto

Links:

Japan had record 610,000 school bullying cases in FY 2019

Suicides top 500 among young students for 1st time ever

Outrage grows over Shiga school’s inaction over bullying

Otsu court finds causal link between bullying, victim’s suicide

2nd probe confirms bullying details, inadequate school response in teen suicide case