Having a child whose first language is English and is currently studying in a Japanese elementary school, the challenges and issues have become quite apparent to me. When it comes to how English is taught in schools, there is a lack of creativity in how it’s taught, a lack of freedom in exploring the language, and a lack of future vision of the language’s benefits.

Our daughter was quite shocked that at Grade 5, they were still learning greetings and very simple sentence construction. She became the go-to person of classmates asking her to pronounce something. They would even ask her to read random English sentences on their lunchboxes or t-shirts and be amazed at the pronunciation.

No need to communicate in English

Much like how our daughter will only master Japanese if we speak it at home, the same goes for Japanese students learning English. However, without extra effort, it’s easy to fall into the comfort of expressing oneself in your first language. If the parents are Japanese they don’t often have the skills to speak English at home.

Thus, the lack of practice leads to a perfect knowledge of grammar from school lessons but minimal conversational skills. Our daughter’s classmates’ parents would often schedule playdates with her so that their children could get better in English in a way that goes beyond the rote learning done in school.

There’s more to English than grammar

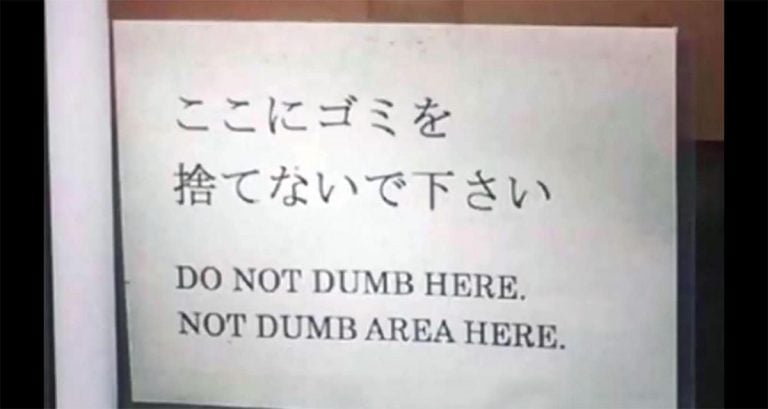

Studying countless hours at an English academy can only do so much, and it’s definitely not enough to grasp the language filled with figurative speech, silent letters, and even confusing concepts without a definite reason aside from “that’s the English way.”

When a teacher says “Repeat after me” and the students follow robotically, that’s not really learning the language. What about the context and application of a particular phrase? A student might be well-equipped with the vocabulary, but does he know when to use it and how? This is where you can find the gap between studying and truly learning the language.

Speaking out loud is at a minimum

In line with the lack of conversational practice, English is taught with an emphasis on reading and writing silently aside from repeating what the teacher says. The lack of freedom in creating sentences, debating, testing out new phrases, or even giving wordplay a try limits the crucial step of application and immersion.

It doesn’t help that the coronavirus pandemic has altered how children engage with one another at school. Nowadays, they limit conversation and don’t speak at all during lunch breaks. There is much room for improvement in how the language is taught when it comes to student engagement.

The lack of need hampers motivation

Another hindrance is the thinking that “I’m Japanese; hence I won’t need English later on,” especially for those who have no plans of studying or going abroad. While numerous people are paying a lot of money to learn Japanese and be able to work here or add it as a skill, the same does not automatically apply vice versa.

Studying a language just to pass exams like Eiken is not enough motivation to immerse in the language. There have been improvements to this approach, such as modifying assessments on entrance exams or pushing high schools and universities to add more practical English to their curriculums.

Perhaps if English is taught in a way that makes students interested in its history and benefits to one’s future life and career, then maybe motivation would increase.

What could be done to address the problem

One of the underlying issues that affect the lack of growth of the English language in Japan is the fear of making mistakes. There’s an understood concept of taking “the Japanese route” of avoiding embarrassment on things such as mispronouncing an English word. Instead of trying to communicate with what they’ve learned, students would miss out on the opportunity due to the fear of making a mistake added to the built-in belief that “everyone is watching you, so you must act perfectly.”

This might seem direct, but it was confirmed when our daughter came home one day asking, “Why do Japanese kids look so perfect? Why are they so serious and mature?” There you go. On a positive note, I was thrilled when our daughter’s school recently hired an English teacher who used to be based in America. She said they’re now doing speeches that the children would curate and deliver in front of the class. It’s reassuring to know that there are some noteworthy progressions on how the country tackles this issue.

Another way to speed up language absorption is by teaching other classes in English, even if it’s one or two sentences here and there. Discriminating English speaking only during English class and Japanese for the rest of the day will stunt growth. Students can better grasp concepts through application such as asking in English, “Do you want another serving of rice” at lunchtime or teaching parts of PE classes in English.

For a country that is so technologically advanced, Japan does have its areas still outdated. With the government’s push for globalization, time is running out for the population to fill in the gap of studying English and using English.