Onomatopoeia stands out as a playful and intriguing phenomenon in the world of languages. At its core, onomatopoeia (オノマトペ) is all about imitating sounds. Derived from the Greek words “onoma” (name) and “poieo” (I do), it means the “creation of a name” based on sounds.

Essentially, onomatopoeias are when a word is formed by imitating the sound associated with its meaning. Think of it like a word that sounds exactly like the noise it’s describing. For example, words like “buzz,” “whisper,” or “bang” in English. These words are not just random; they are crafted to mimic the sounds they represent.

Every language has its own set of onomatopoeic words, and this is where it gets really interesting. Different cultures interpret sounds in their unique ways, often influenced by the phonetic structure of their languages. For instance, while English speakers hear a dog’s bark as “woof,” a Japanese speaker might hear it as “わんわん” (wan wan), and a Korean speaker as “mung mung.” This difference shows how culture and language shape our perception of sounds.

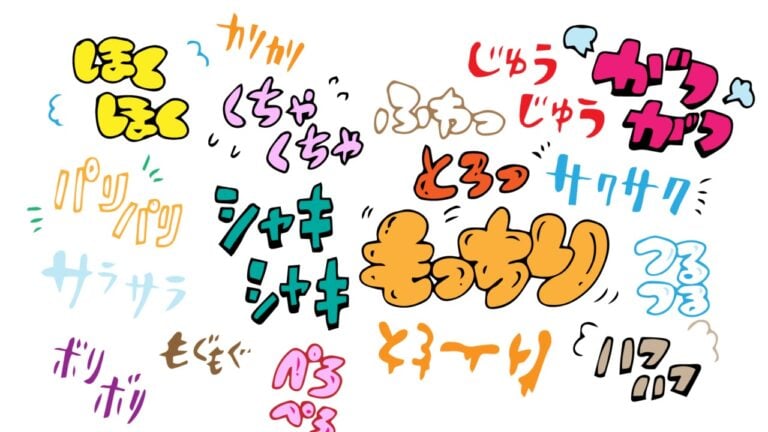

Onomatopoeias are not just limited to mimicking sounds. They can also express sensations, emotions, or actions. For example, in Japanese, words like “キラキラ” (kirakira) represent the glittering of light, even though glittering doesn’t have an actual sound. This usage broadens the role of onomatopoeias in a language, allowing them to paint vivid pictures and evoke sensory experiences.

For language learners, onomatopoeias are both fun and challenging. They are fun because they are often easy to remember and mimic. However, they can be challenging due to their unique and sometimes non-standard structure compared to other words in the language.

In this article, let’s explore onomatopoeias and how they have unique impacts and use within a Japanese language context.

What is the Japanese Twist on Onomatopoeias?

Japanese take onomatopoeia to an impressive level. The language doesn’t just use these sound words for mimicking noises; it extends them to describe movements, feelings, and states of being. There are several types of onomatopoeias in Japanese, each serving a unique purpose:

- 擬声語: These imitate sounds made by living things, like animals or humans. For instance, a dog’s bark is “わんわん” (wan wan), which is akin to “woof” in English.

- 擬音語: This type represents sounds from inanimate objects or nature, such as the sound of rain “ザーザー” (zaa zaa) or the rustling of leaves “サワサワ” (sawa sawa).

- 擬態語: Gitaigo describes conditions or states, like “ツルツル” (tsuru tsuru) for something smooth and slippery.

- 擬容語 : These are for movements and actions, like “クルクル” (kuru kuru) to depict something going round and round.

- 擬情語: This type relates to emotions or feelings. An example is “ドキドキ” (doki doki) for a racing heart.

Examples of Japanese Onomatopoeia:

- Animal Sounds: A rooster’s crow is “コケコッコ” (kokekokko), while a cat’s meow is “ニャン” (nyan).

- Nature Sounds: Rain sounds are expressed as “パラパラ” (para para) for light rain or “ジトジト” (jito jito) for continuous rain.

- Conditions and States: A shiny, sparkling surface might be described as “キラキラ” (kira kira).

- Movements: “クルクル” (kuru kuru) can represent turning or spinning around.

- Emotions: Feeling excited or thrilled can be expressed as “ワクワク” (waku waku).

What are the Japanese Cultural Significance and Usage of Onomatopoeias?

What’s particularly interesting about Japanese onomatopoeia is its deep integration into the language and culture. These words are not just fun or playful additions but essential components of everyday communication, capturing sound, emotion, and action nuances. Let’s look at the following example sentence:

休みの日に家でごろごろする

Yasumi no nichi ni ie de gorogoro suru

“On my day off, I laze around the house”

Here the onomatopoeia in question is ごろごろする. Here the word is used to describe a state of laziness or idleness. The word originally stems from the sound associated with rolling or rumbling, such as thunder. However, the auditory imagery has been extended metaphorically in Japanese to describe a state of lounging or idling, suggesting a person rolling around leisurely without purpose. Such extensions of onomatopoeic words to describe actions or states beyond their original sound-based meanings are quite common in Japanese.

Japanese onomatopoeia can be combined with verbs, turned into adverbs, or even used as standalone expressions when used in sentences. Their use is not strictly governed by strict rules, and they can appear in various forms, often written in katakana for emphasis or hiragana for softer sounds.

When looking at Japanese onomatopoeias within the perspective of linguistics and sensory perception, as done by Mitsuhiko Hanada in her 2016 article “Using Japanese Onomatopoeias to Explore Perceptual Dimensions in Visual Material Perception”, Japanese onomatopoeias offer another unique intersection.

While “ごろごろ” (gorogoro) was used as a metaphoric extension, they can also be extended to depict a wide range of sensory experiences, including the perception of material properties. Japanese onomatopoeias are not just auditory but also capture tactile and visual sensations. For instance, the sound word “ザラザラ” (zara-zara) might represent the rough texture of a surface visually and to the touch.

This means we can infer material properties like roughness or smoothness through verbal descriptions and auditory cues, not just by touch. Different onomatopoeias can describe the same material in various states. For example, a wet surface might be described as “ねばねば” (neba-neba) while a dry, rough surface could be “カサカサ” (kasa-kasa). This specificity in onomatopoeias enhances our understanding of material properties beyond visual appearances, incorporating tactile experiences into our perception.

However, this creates unique challenges when translating and studying Japanese onomatopoeias from the context of other languages, like English or Spanish. These words often capture specific sensory experiences or cultural nuances that don’t have direct equivalents in other languages.

In literature, the translation of onomatopoeias can significantly affect the tone and style of the piece. For example, Haruki Murakami’s works, rich in onomatopoeic and mimetic expressions, require careful translation to maintain their original essence and emotional impact. These nuances may be related to Japanese perceptions of sound, movement, or material properties, which may not have direct parallels in other cultures.

While studying Japanese, don’t overlook onomatopoeias. Not only do they add fun to your studies, balancing the challenging task of learning kanji, but they’re also crucial for effective communication and essential for achieving fluency in the language.

Links:

- Using Japanese Onomatopoeias to Explore Perceptual Dimensions in Visual Material Perception by Mitsuhiko Hanada

- Translating Japanese onomatopoeia and mimetic words by Hiroko Inose.

- The Sound-Symbolic System of Japanese (Ideophones, Onomatopoeia, Expressives, Iconicity) by Shoko Saito Hamano