When I was 20 years old, I spent one year studying in Japan. At the time, I was a third-year American college student, but for that year, I had the opportunity to study at Nara University of Education.

Although I was an exchange student, I had the opportunity to take classes with peers, live in a dorm full of other students from all around the world, and best of all, live full time in Japan

In fact, I loved it so much, now I am a full time student at Kyoto University

In this article, I would like to explore universities in Japan, with a focus on Kyoto University. I will discuss what sets it apart from both American universities and other Japanese universities, as well as my own personal experiences as a “Kyoudaisei” (京大生 or Kyoto University student).

What is Kyoto University?

Kyoto University, nicknamed Kyodai, is one of the oldest and most prestigious universities in Japan, founded in 1897 as Kyoto Imperial University. Over the years, it has gained a reputation for excellence in research, teaching, and innovation and has produced many notable alumni, including twelve Nobel laureates, two Fields Medalists, and one Gauss Prize laureate.

Its history can be traced back to 1869 when the Kyoto Prefectural School of Medicine and the Kyoto Prefectural School of Science were established by the newly-formed Meiji government.

In 1897, these two schools were merged to form Kyoto Imperial University, which was one of the first imperial universities established in Japan. The university initially had five faculties: Letters, Law, Science, Medicine, and Engineering.

During the early 20th century, Kyoto Imperial University underwent significant growth and expansion, with the addition of new faculties and research institutes. It also played a prominent role in Japanese society, producing many prominent scholars, scientists, and political figures.

After World War II, Kyoto Imperial University was renamed Kyoto University, and it became a national university under the new Japanese education system. In the postwar period, Kyoto University continued to expand and develop, becoming a leading research institution in Japan and the world.

In the 20th century, a group of Japanese philosophers associated with Kyoto University, known as The Kyoto School, developed a distinctive approach to philosophy that blended Western philosophical ideas with traditional Japanese philosophy and religion. The Kyoto School emerged in the early 20th century and was active until the 1960s.

The Kyoto School philosophers were influenced by the works of Western philosophers such as Immanuel Kant, Friedrich Nietzsche, and Martin Heidegger, as well as traditional Japanese philosophy and religion, particularly Zen Buddhism. They sought to develop a new form of philosophical inquiry that could bridge the gap between these entirely separate traditions.

The Kyoto School is associated with several key figures, including Nishida Kitaro (西田幾多郎), Tanabe Hajime (田辺元), and Nishitani Keiji (西谷啓治). These philosophers developed a range of concepts and ideas, including the idea of “absolute nothingness” (無), the critique of modernity, and the idea of “self-emptying” (kenosis).

Differences between Japanese and American Universities

There are several differences between universities in Japan and universities in America. Coming from a “party college” in America, I was amazed that the idea of a “party college” was foreign to my Japanese friends and classmates. I remember walking past Greek life that was often filled with laughter and music every weekend or hearing many tales of my friends’ night out getting wasted. In contrast, in Japan, most of my friends rarely ever partied, and when they did go out for social drinks, the party would end by 11 pm.

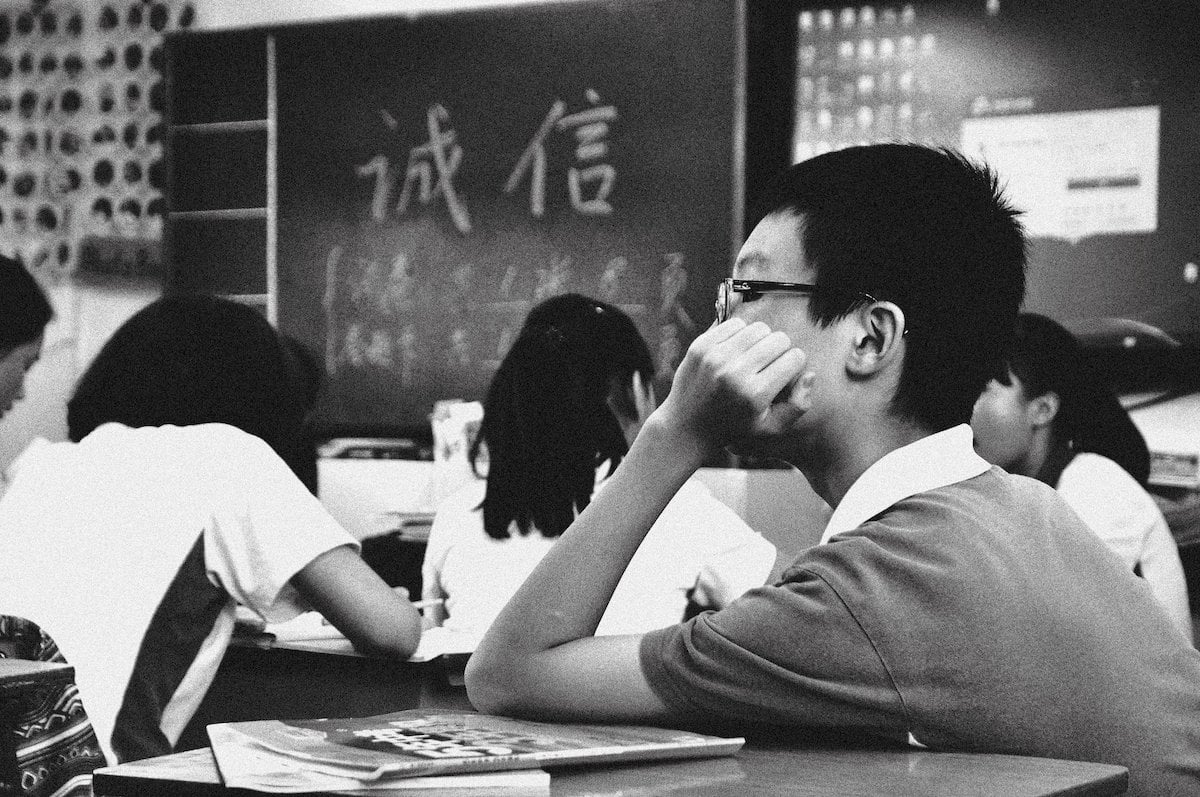

Upon entering Japanese universities, the first culture shock you may have comes before you even enter the university – admissions. Admissions to Japanese universities are often based primarily on entrance exams, which are highly competitive and require extensive preparation.

In contrast, American universities consider a wider range of factors in admissions, including grades, test scores, extracurricular activities, essays, and letters of recommendation.

For someone like me, who does poorly on tests, this made applying to Kyoto University so daunting. I ended up studying for five months straight and nearly cried halfway through!

The next thing I noticed quickly coming to Japan was that Japanese universities have a more formal and hierarchical academic culture, with a greater emphasis on respect for authority and adherence to rules and procedures.

In contrast, American universities tend to have a more informal and collaborative academic culture, with a greater emphasis on independent thinking and creativity. For example, it’s common for students in my American college to refer to their professors informally, while the thought of doing such in Japan is absurd.

Another major difference I noticed is that in Japan, the curriculum is often more structured and standardized, with less flexibility for students to choose their own courses or explore different fields. Many of my Japanese classmates often have set curriculums throughout their college experience (although this does depend on the university as I found Kyoto University was less this way than others).

In contrast, American universities tend to offer more flexibility and choice in the curriculum, allowing students to tailor their education to their interests and goals.

One of the differences that has caused me the biggest problems is that Japanese universities often rely heavily on lectures and rote memorization, with less emphasis on discussion and critical thinking. As someone with a terrible memory, I have struggled extremely with the strong emphasis on tests rather than class discussions and essays. Luckily, most of my master’s level classes in Kyoto have been presentation and essay-based more than exams, but if I see an exam on the syllabus, I panic because Japanese professors expect you to be able to memorize everything!

The last difference I noticed is the fact that Japanese universities are significantly less diverse than American. At my first university, there were perhaps only thirty or forty foreign students who all lived in the same dorm. It was quite a shock after coming from an American university, which is famous for its diversity and vibrant campus cultures, with a wide range of social and extracurricular opportunities for students. However, the lack of diversity luckily did nothing to hinder my ability to make friends.

Differences between Kyoudai and Toudai

Of course, when discussing the rivalry between Kyoto University and the University of Tokyo, I must admit upfront that I am obviously biased as a Kyoto University student. But I’ll refrain from saying that Kyoto University is better!

However, it is true that both Kyoto University and the University of Tokyo are highly regarded and prestigious universities in Japan. Kyoto University is known for its strengths in the fields of humanities, environmental studies, and life sciences, including biotechnology, medical research, and neuroscience. Likewise, the University of Tokyo is known for its strengths in a wide range of fields, including science and engineering. Both are very well-developed research institutions, but they have different research priorities and strengths. Kyoto University has a strong focus on interdisciplinary research and is known for its innovative research in fields such as stem cells and regenerative medicine. On the other hand, the University of Tokyo has a strong focus on basic research and is known for its contributions to fields such as physics, chemistry, and mathematics.

One of the biggest differences is in campus culture. Kyoto University, like the rest of Kansai, has a more relaxed and laid-back campus culture with a strong focus on traditional Japanese culture and arts. In comparison, the University of Tokyo has a more competitive and rigorous campus culture, with a strong focus on academic achievement and research excellence. This, in many ways, reflects the culture of the cities they are in. Kyoto University is in Kyoto, which is a smaller and more traditional city with a slower pace of life. The University of Tokyo is in Tokyo, which is a larger and more modern city with a faster pace of life.

Despite these cultural differences between the universities, there is one commonality I always hear about them. Often, both are known to having responsible and highly intelligent students, but it is also said that students at both universities are crazy!

What’s struggles do I have as a foreigner on Kyoudai Campus?

This is the most difficult section to write. For one, I am quite happy in my life at Kyoto University. I have had many opportunities that I would not have had at home, many classmates that have changed my life, and amazing professors from whom I have learned quite a bit. This makes it hard to shed light on the things I have personally struggled with. I would like to preface this section by first saying that while there are significant struggles to deal with, this isn’t me saying that the program is all bad.

With that said, I have to mention that equal treatment between foreign students and Japanese students does not exist. For one, I was surprised to learn that the requirements for foreign students are not the same. For example, it is uncommon for foreign students to be required to be a TA and teach classes. This removes foreign students from the opportunity to gain experience in leadership positions. For some foreign students, this is a blessing, but for others, it can be a struggle when they want the same opportunities and experiences as the Japanese classmates but immediately get overlooked.

The reason for this is a bit complex, as some foreign students are unable to speak Japanese, making it impossible to teach in a Japanese class and lead Japanese groups. This is the double-edged sword of having a program without explicit language requirements. There are very few English classes, and many Japanese students on campus have low proficiency or low motivation in English studies. The same is within the administration as it is often required for foreign students to have a tutor, which is a student (most of the time Japanese students, but also at times high Japanese proficiency international students) at Kyoto University who acts as a translator when handling office officials unable to speak English.

Likewise, this can be a struggle on the social side as many Japanese students and professors automatically assume foreign students have little to no Japanese ability. This means some Japanese students actively avoid direct interactions, and foreign students can easily get isolated from their peers even if they have a decent Japanese proficiency.

While not all faculties are the same (there is a lot of diversity even within the same university), the divide between Japanese and foreigners is perhaps the biggest struggle. In some labs, this results in the minority foreign student population being isolated into their own pockets with difficulty making strong connections to their Japanese peers. While this might be fine if you are doing a temporary foreign exchange program (albeit a bit disappointing), it can be more frustrating when you are an international student.

The other difficulty comes from the strictness of the Japanese language itself. In every language, second language speakers naturally have differences in their language use from their native counterparts. For example, word choice, grammatical structure, accents, and so on can all mark a foreign language user as having their own unique dialectic category. English spoken within Japan is different than in China or India. English is, in fact, an international language with a multitude of foreign native and non-native dialects, making it a very adaptable language to use.

While of course prejudices and biases about different dialects in English exist, it is undeniable that English has a natural vast diversity in use, especially compared to monolithic languages like Japanese. Japanese has dialectic differences across regions, but there is a big difference in that Japanese does not have a lot of international dialects in the way English does. This means that when foreigners gain high Japanese proficiency and start entering Japanese spaces, there is much less acceptance of diverse accents and use.

This is something that many foreigners struggle with when submitting academic papers, applications, and other materials in Japanese, as the critique they receive, regardless of how many native speakers proofread their writing, can be harsh. This can lead to many students feeling discouraged from even attempting to use and improve their Japanese ability, as the effort to use the language can result in falling behind and facing unnecessary hurdles.

How is it changing?

While I will admit that, at least in my faculty, active efforts to address and change these types of problems have been made – such as increased encouragement for English within academic circles (given that international research requires adequate English proficiency), pushes to include foreign students with Japanese proficiency in leadership positions, and encouragement to increase Japanese and foreign student social interactions.

I have noticed that there’s big pushes to increase global connections across campus and I do think the university is very good at trying to promote foreign exchange and collaborations. As the world is exiting the global pandemic, the number of foreign students (both foreign exchange and international students) on campus has increased and I hope in turn this will be able to benefit everyone.

However, many of the problems on campus I’ve notice are, in part, a microcosm of the difficulty of life as a foreigner throughout Japanese society. The monolithic culture can often be very exclusionary for those who do not fit the “Japanese ideal” which, as I have discussed in past articles, harms both Japanese and foreigners alike.