Japan lacked a writing system before the introduction of kanji from China. In the fifth century, kanji found its way to Japan via the Korean peninsula, marking the emergence of the oldest historical records known as the Kojiki (712) and Nihon Shoki (720). These influential works were dedicated to capturing the essence of ancient Japanese mythology, folk songs, and historical accounts.

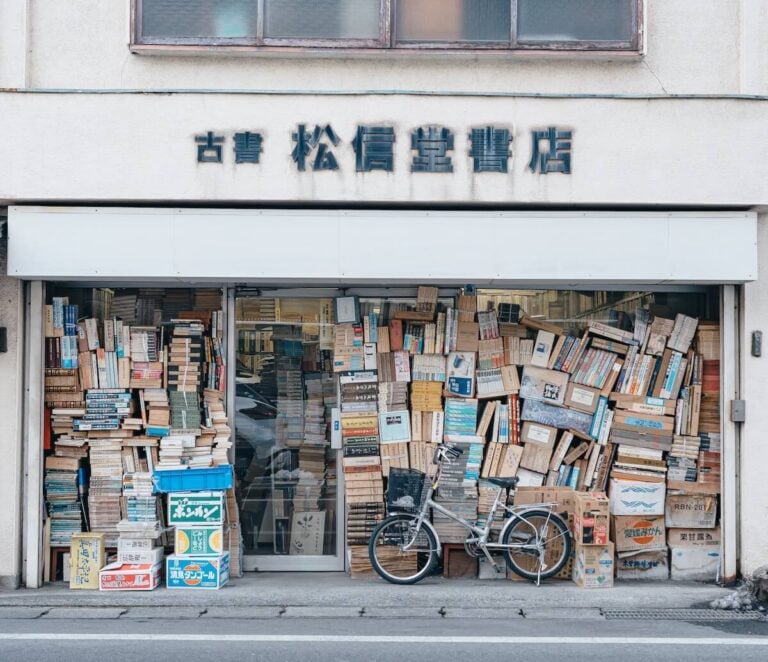

It was during the Heian period (794-1185) that the world witnessed the birth of the first novel, The Tale of Genji (源氏物語), written by a female courtier named Shikibu Murasaki. Since then, Japan has developed a rich literary history that explores various aspects and experiences of Japanese culture.

Literature is crucial in preserving and transmitting a culture’s history, values, traditions, and beliefs across generations. In the case of Japan, understanding its rich literary history is important for those seeking a deeper insight into its culture. In this article, we delve into the history of literary works in Japan, shining a light on the authors who have contributed to its cultural tapestry.

Ancient Literature (until the 8th century)

Before the Heian period, Japanese literature was predominantly written in Chinese. The influence of the Chinese language and literature on Japanese culture was substantial during early Japanese history (such as the Nara period around 710-794), leading to the adoption of Chinese literary traditions in early Japanese works. These works often utilized a blend of classical Chinese and early Japanese language, following the framework and structure of Chinese historical chronicles. This integration of the early Japanese language into the texts of that era exemplifies the progressive development of Japanese writing.

Kojiki (The Record of Ancient Matters): Compiled in the eighth century, this collection comprises myths, legends, and historical accounts that shed light on Japan’s creation and early history.

Nihon Shoki (The Chronicles of Japan): Completed in 720, this historical record provides a comprehensive narrative of Japanese mythology and history.

Manyoshu (Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves): This anthology is the oldest surviving collection of Japanese poetry, featuring works from the third to the eighth century.

Heian Period (794-1185)

During the Heian period, both Japanese and Chinese found their place in written works. Chinese characters, known as kanji, held prominence in official documents, Buddhist texts, and Chinese poetry. On the other hand, the Japanese language, referred to as “waka” or “Yamato kotoba,” thrived in courtly poetry, diaries, essays, and narratives. This period witnessed the emergence of a distinct Japanese literary tradition as the use of Japanese in literature grew. This time period’s literature often portrayed the aristocracy’s refined courtly life, delving into themes of romance, beauty, and intricate relationships. It eloquently depicted the experiences and emotions of noble characters. Notably, women writers played a significant role in shaping Heian Period literature.

The Tale of Genji (源氏物語):

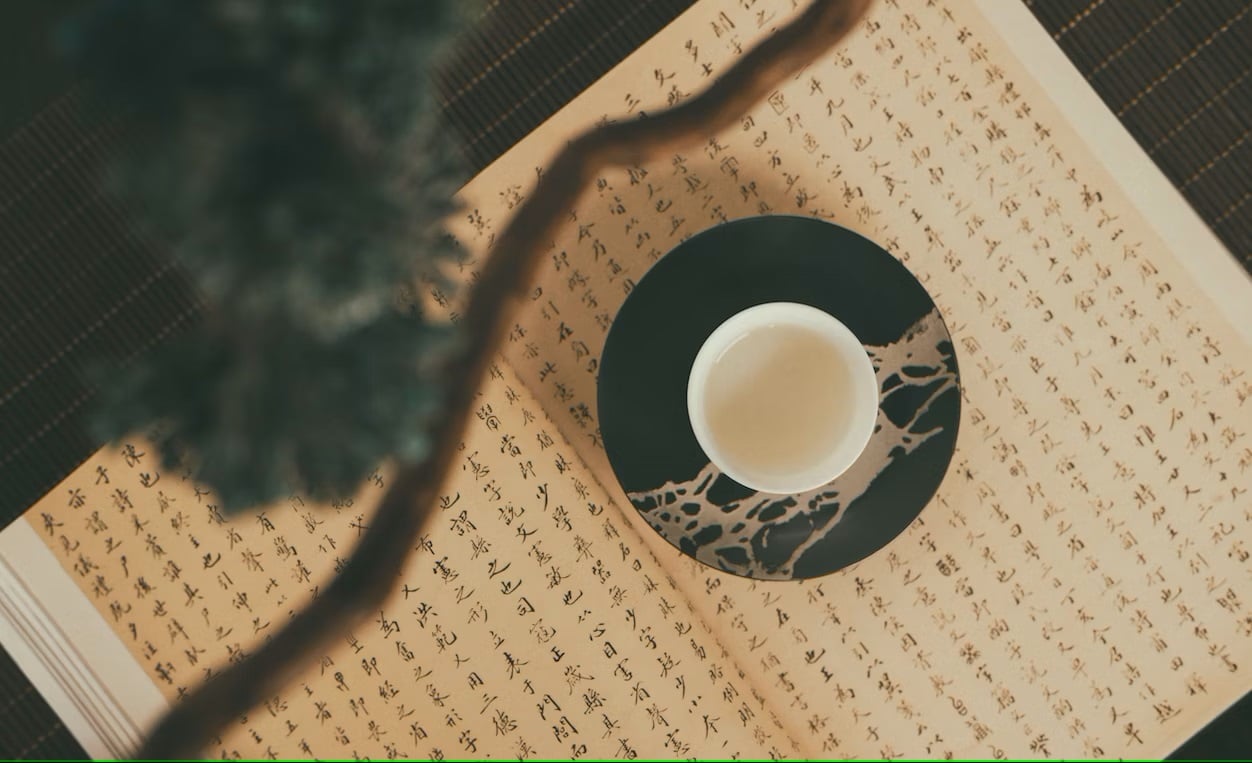

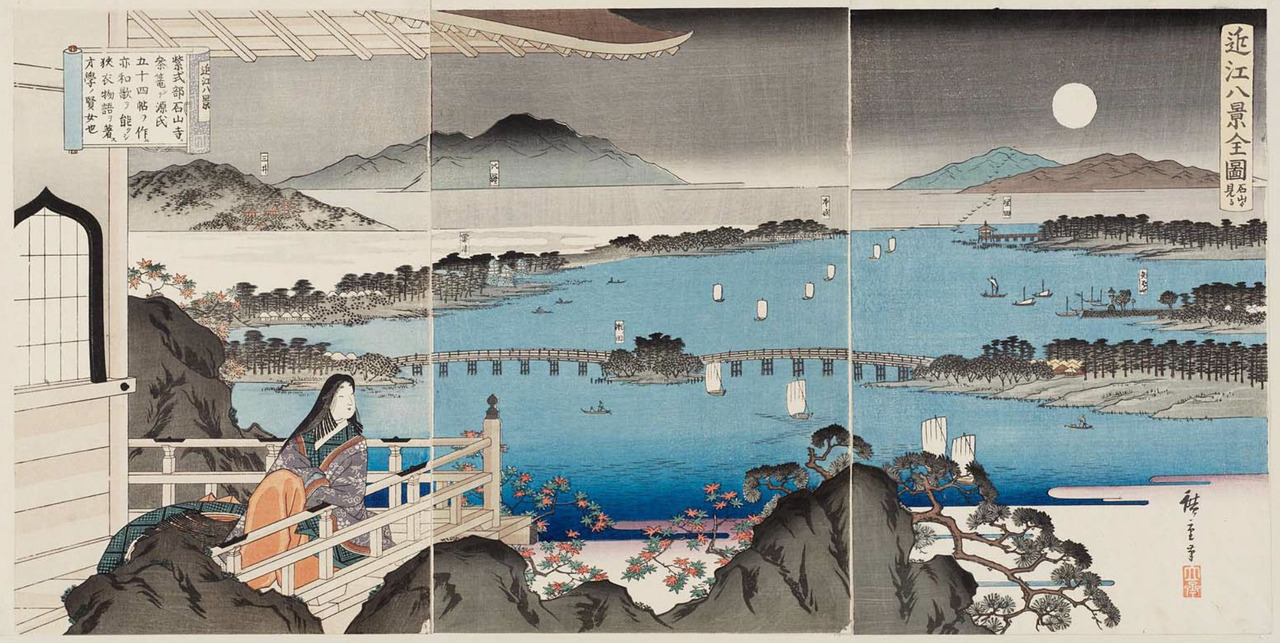

As mentioned before, Shikibu Murasaki, a prominent figure in Japanese literature, holds a significant place in history as the author of “The Tale of Genji,” widely regarded as the world’s first novel and a masterpiece of the Heian period.

Immersing herself in the literary and poetic world, Shikibu Murasaki thrived during her time at court. Her extensive education and profound familiarity with Chinese and Japanese classics shaped her writing prowess. “The Tale of Genji,” her magnum opus, emerged during the early 11th century and encompassed over 1,000 pages in its complete form.

This epic narrative revolves around the life and amorous escapades of the captivating and gifted nobleman Hikaru Genji. Within its pages, the novel delves into profound themes of love, relationships, courtly life, beauty, and the transient nature of existence. It paints a vivid picture of Heian court culture, capturing its customs and intricacies with remarkable detail.

Over time, this book has seen many adaptations, such as manga, anime, and live-action. Personally, I am biased towards my affection for the 1987 anime adaptation for its beautiful animation and subtle exploration of the story, but it is good to be familiar with the story.

Murasaki depicted at Ishiyama-dera by Hiroshige III (1880)

The Pillow Book (枕草子):

Sei Shonagon, another notable figure in the Heian period, shared Shikibu’s passion for writing. As a courtesan, she became renowned for her literary work, “The Pillow Book.” This collection displays a wealth of observations, anecdotes, and personal reflections on court life.

Born into a noble family in the late 10th century, Sei Shonagon held the esteemed position of a lady-in-waiting to Empress Teishi, consort of Emperor Ichijo. Renowned for her sharp wit, intelligence, and perceptive observations, she carved a prominent role within the imperial court.

Completed around the early 11th century, “The Pillow Book” is a unique and multifaceted creation that defies easy classification. Its contents consist of fragmented writings encompassing a wide range of topics. From detailed lists and descriptions of court ceremonies and customs to contemplations on nature, beauty, gossip, and personal anecdotes, the book presents a vibrant and intimate portrayal of courtly existence during the Heian period.

Sei Shonagon in a later 13th-century painting

Zen Buddhism and Literature

During this period, Zen monks significantly shaped literature by emphasizing simplicity, directness, and the concept of “enlightenment through everyday activities.”

Zen-inspired themes and aesthetics left a lasting impact on various literary forms, including prose and poetry. Writers, such as the monk Kamo no Chomei (鴨 長明), infused their works with Zen ideas, emphasizing the impermanence of life, the fleeting nature of worldly attachments, and the quest for inner peace.

Kamo no Chōmei, by Kikuchi Yōsai

Waka and linked verse

During this period, the practice of composing poetry in fixed forms, such as tanka and renga, gained popularity.

Renga, also known as “linked verse,” emerged as a collaborative poetic form during Japan’s medieval period. It involves multiple poets taking turns composing alternating stanzas. The hokku, which serves as the opening verse, sets the tone and theme for the poem.

Conversely, Tanka is a standalone poetic form that predates renga and is often regarded as its predecessor. It consists of five lines structured with a syllable pattern of 5-7-5-7-7. Tanka poetry traditionally evokes emotions, explores nature, and delves into love, longing, and transience themes.

Edo Period (1603-1868)

The Edo period, one of the most famous periods in Japanese history, witnessed urban culture flourishing. This was a period of peace and stability under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate, characterized by strict social hierarchy, isolationist policies, economic growth, and the flourishing of arts and culture. It encompassed a variety of genres, such as haiku, kabuki plays, ukiyo-e prints, and popular fiction that reflected the time’s vibrant and diverse literary landscape.

Haiku:

The Edo period witnessed the flourishing of a minimalist form of poetry known as haiku, characterized by its 5-7-5 syllable structure. Haiku originated from hokku; the opening stanza of a collaborative linked verse called renga. Over time, hokku also referred to as the “starting verse,” gained recognition as an independent form of poetry.

Among the most renowned and influential haiku poets in Japanese literature is Matsuo Basho (松尾 芭蕉, 1644-1694). Basho is widely regarded as a master of the haiku form and is often hailed as the greatest haiku poet. His contributions have profoundly shaped the development and understanding of haiku.

Born in the Iga province, which is now part of Mie Prefecture in Japan, Basho embarked on his literary journey as a poet, immersing himself in the study and composition of hokku within the collaborative linked verse tradition of renga. However, he eventually shifted his focus to crafting stand-alone haiku, wanting to explore the essence of a singular moment and evoke a profound connection with nature and the human experience.

Basho’s impact on haiku extends beyond his poetic compositions; his critical writings also played a significant role. Among his most famous works is “Oku no Hosomichi” (The Narrow Road to the Interior), a travelogue in prose and haiku. This literary masterpiece chronicles Basho’s journey through the northern provinces of Japan, capturing his vivid observations of nature, encounters with diverse individuals, and reflections on the transient nature of existence.

Statue of Basho Matsuo, by Hokusai Katsushika

During the Edo period, hokku, the opening stanza of renga, experienced notable transformations in both form and content. Previously, hokku adhered to strict rules concerning syllable count and meter. However, over time, it transitioned towards a more flexible structure. Additionally, the purpose of hokku shifted from solely serving as an introduction to renga to being recognized as a standalone poem with unique attributes. Reflecting these changes, the term “haiku” emerged in the latter half of the 19th century to describe the evolving nature of the form.

Ukiyo-zoshi:

Ukiyo-zoshi and gesaku are two literary genres that emerged during Japan’s Edo period (1603-1868), offering captivating fiction to a broad audience, and reflecting the vibrant urban culture of the time.

Ukiyo-zoshi, meaning “tales of the floating world,” was a highly popular genre of fiction that thrived in the bustling urban centers of Edo (present-day Tokyo) and Kyoto. These narratives portrayed the lives and adventures of common people, often centering around the entertainment districts and pleasure quarters, capturing the allure of transient pleasures.

Distinguished by its use of vernacular Japanese instead of classical Chinese, ukiyo-zoshi made literature more accessible to a wider readership. The stories employed colloquial language and vivid descriptions to vividly depict urban life’s sights, sounds, and customs. Lively and humorous narratives abounded in these works, blending elements of romance, adventure, satire, and social commentary.

One notable example of ukiyo-zoshi is “Ukiyo Monogatari” (Tales of the Floating World) by Asai Ryoi (浅井 了意). This work presents a collection of vignettes that encompass the various facets of urban life, providing glimpses into the diverse experiences and colorful characters of the time.

Illustrated page of a ukiyo-zōshi novel by Nishikawa Sukenobu

Gesaku:

Gesaku encompasses a broader category of popular fiction that includes Ukiyo-zoshi and other forms of prose literature, poetry, and theatrical works. This diverse genre incorporates a range of styles, ranging from humorous stories to satirical essays, parodies, and light-hearted poetry.

Like Ukiyo-zoshi, gesaku works aimed to captivate and entertain a wide audience. These writings often featured lively, humorous narratives, employing wordplay, puns, and satirical commentary on societal norms and conventions. It became popular within Gesaku to portray commoners as protagonists or to mock the privileged elite.

One notable example of gesaku is “Tokaidochu Hizakurige” (Shank’s Mare), a comical travelogue written by Jippensha Ikku (十返舎 一九). The story follows the misadventures of two travelers as they journey along the Tokaido road, providing an entertaining and humorous account of their escapades.

Meiji Period and Modern Literature (1868-present)

The Meiji Restoration marked a pivotal period in Japan’s history, triggering profound social and cultural transformations. During this era, Japanese literature experienced a significant shift as it embraced new influences from Western cultures and delved into a diverse range of topics, including the complexities of human nature. Japanese writers explored diverse themes such as human nature, identity, morality, individualism, and the clash of tradition and modernity. Their works ranged from introspective novels to political satires, reflecting a remarkable diversity in literary expression.

Naturalism and Realism:

Drawing inspiration from European literary movements like French naturalism, naturalism aimed to present an objective and scientific depiction of life. It embraced a deterministic perspective, highlighting the impact of heredity, environment, and social forces on human behavior and social conditions.

Among the notable realist writers of the Meiji era, Ichiyo Higuchi stands out. She was recognized for her short stories that focused on women’s lives in lower-class society, delving into themes of poverty, gender roles, and social constraints. Higuchi’s works offered a poignant glimpse into the realities faced by marginalized individuals within Japanese society.

Both naturalism and realism revolutionized Japanese literature by challenging traditional literary norms and introducing a new level of social critique and psychological depth. These movements allowed writers to engage with contemporary issues and delve into the complexities of human existence within a rapidly changing society.

Among the notable authors of this period are Ryunosuke Akutagawa (芥川龍之介), Natsume Soseki (夏目漱石), Osamu Dazai (太宰治), and Ogai Mori (森鴎外).

Postwar Literature:

Postwar literature in Japan encompasses the literary works produced after the conclusion of World War II in 1945. This period is characterized by its diverse themes, styles, and approaches as writers grapple with the aftermath of war, the challenges of reconstruction, and the evolving social and cultural landscape.

In the wake of the war, literature explores the profound impact on individuals, families, and society as a whole. Writers delve deep into the physical and emotional wounds inflicted by the war, addressing themes of loss, trauma, guilt, and the struggle to reclaim identity amidst the devastating aftermath.

With a genuine fascination with humanity and existential inquiries, writers of this era wrestled with the nature of human existence, confronting questions of morality and searching for meaning in a world turned upside down. They delve into profound topics such as alienation, loneliness, and the quest for purpose.

Many postwar writers fearlessly critique societal issues, confronting social class, poverty, inequality, and the challenges accompanying rapid industrialization and urban expansion. They navigate the intricate complexities of postwar life, shedding light on the struggles of marginalized individuals and criticizing outdated institutions that fail to address new realities.

This era of writers embraces experimentation and innovation, exploring fresh styles, techniques, and narrative structures. They form part of an avant-garde movement that defies traditional literary conventions, pushing the boundaries of form, language, and subject matter.

Some notable authors associated with postwar Japanese literature include Yasunari Kawabata (川端 康成, having received a Nobel Prize in Literature in 1968), Kenzaburo Oe (大江 健三郎), Fumiko Enchi (円地 文子), and Kobo Abe (安部 公房).

Recommended Readings!

Prior to conducting research for this article, I reached out to a Japanese friend for their recommendations, and I would like to express my gratitude for their valuable input. With their guidance, I have compiled a list of suggested readings. However, it’s important to note that this list is by no means exhaustive. Japanese literature boasts a rich history dating back to 1008 CE; delving into its vast depths could occupy a lifetime. Nevertheless, consider exploring one of the following books if you’re looking for a starting point.

Shikibu Murasaki “The Tale of Genji”

This work serves as the inspiration for countless stories in girls’ manga! It holds a position of utmost authority in Japanese classical literature. However, it should be noted that its extensive length can make it a challenging read, particularly if you’re attempting to tackle the original Japanese text.

[Amazon Link: https://a.co/d/6dsrg0K]

Natsume Soseki “Kokoro”

Soseki is an immensely renowned novelist whose works come highly recommended to anyone with an interest in Japanese literature. His books delve into the profound identity crisis experienced by the Meiji era elites as a result of rapid Westernization.

[Amazon Link: https://a.co/d/23bskgR]

Ogai Mori “The Dancing Girl”

This story explores the clash between Western ideals and traditional Japanese values. The story explores the struggles faced by its protagonist, Otama, a young geisha who becomes involved with a Japanese student studying in Germany and becomes pregnant by him.

[Amazon Link: https://a.co/d/45709Zc]

Osamu Dazai “No Longer Human”

Osamu Dazai, through his notable works such as “No Longer Human” (Ningen Shikkaku), “The Setting Sun” (Shayō), and “The Beautiful Girl” (Bannen), delves into a range of profound themes concerning human nature, social alienation, and existential crises. His writings explore dark aspects of self-destructive tendencies and psychological struggles, offering a poignant reflection of the disillusionment and hypocrisy prevalent in post-war Japan. While I have personally only read “No Longer Human,” it has undoubtedly become one of my favorite novels.

[Amazon Link: https://a.co/d/eQeHr3h]

Ichiyo Higuchi “Takekurabe”

Ichiyo Higuchi, the pioneer of feminist literature, is the face on the 5,000 yen bill in Japan. Her renowned novel, “Takekurabe” (Growing Up or Child’s Play), offers a glimpse into the lives of young individuals navigating Tokyo’s late 19th-century urban landscape. Through this work, Higuchi skillfully explores the profound transition from childhood to adolescence amid socioeconomic inequality. Her thought-provoking themes beautifully intertwine to present a poignant depiction of youth, societal dynamics, and the unique challenges those growing up face amidst Meiji-era Tokyo’s rapidly changing urban environment Meiji-era Tokyo’s rapidly changing urban environment.

[Amazon Link: https://a.co/d/1JAyRzj]

Atsushi Nakajima “The Moon Over the Mountain”

Atsushi Nakajima (1909-1942), a renowned Japanese writer and poet of the early 20th century, left a lasting impact with his literary contributions. Nakajima weaves together influences from classical Chinese literature in one of his notable works, a novella set in ancient China. His background as a poet shines through in the lyrical and poetic language employed throughout the story, adding a captivating layer to the narrative. This unique blend of traditional Chinese storytelling and a distinctly Japanese sensibility results in an evocative and thought-provoking work, leaving a lasting impression on readers.

[English Book: https://a.co/d/0CK97pQ]

[Bilingual Book: https://a.co/d/bD98BeV]

Kenji Miyazawa “Night on the Galactic Railroad”

“Night on the Galactic Railroad” is a renowned novella by Kenji Miyazawa (1896-1933), a highly esteemed Japanese author and poet. Regarded as one of Miyazawa’s most cherished works, it has captured the hearts of many readers. The narrative centers around the extraordinary expedition of two young boys, Giovanni and Campanella, as they embark on a fantastical voyage aboard the Galactic Railroad. The railroad symbolizes life’s journey and becomes a metaphorical vessel for exploring profound themes of friendship, self-discovery, and the fundamental nature of existence.

[Amazon Link: https://a.co/d/i9MKc8P]

Yumeno Kyusaku “Hell in a Bottle”

“Hell in a Bottle” is a haunting and atmospheric tale that delves into the depths of guilt, punishment, and psychological torment. The story takes us on a journey alongside the protagonist as he enters a mysterious world confined within a bottle. Within this confined space, he encounters a series of grotesque and nightmarish events, confronting strange beings and facing the weight of his own sins and remorse. Yumeno Kyusaku challenges our perception of reality and delves fearlessly into the darker aspects of the human condition. Through “Hell in a Bottle,” Yumeno’s exploration of the subconscious mind unravels the intricacies of human desires, fears, and guilt, leaving an impression on readers.

[Amazon Link: https://a.co/d/1RmgMub]