“If I had to describe myself in terms of weather, I would say that I am slightly cloudy. Clear skies are pleasant, but clouds create light and shadows, giving the sky various expressions. It may not have the power to attract people in a flash, but it is always nearby and never gets boring. Perhaps that is the kind of person I want to be.” (Translation of “Saya Hiyama, a unique caster who aspired to be a voice actress, overflows with love for manga and anime” Link

Weather forecaster Saya Hiyama introduced herself with charisma. She gained widespread recognition throughout Japan when a video showcased her seamlessly transitioning from her playful persona to delivering a serious breaking news report on a severe natural disaster.

Her adorable moments quickly became internet sensations, thanks to her nerdy hobbies, love for anime, slightly shy demeanor, and charming antics. She became an endearing role model and a dream girl for the average Japanese guy navigating the complexities of romance.

Adding to her appeal was the fact that she appeared to be single.

However, the downside of fame became evident as some of her millions of fans took their admiration to extremes. This occurred when a highly anticipated Weather News Live fan meetup was approaching, the first in five years, featuring all the casters, including Saya.

About a week before the fan meetup, something unusual occurred. Saya mysteriously disappeared from Weather News Live. Fans were bewildered when they saw photos of her in Great Britain watching Wimbledon from seats typically reserved for friends and family.

This was a surprising revelation, as she had never shown an interest in tennis before. She was watching a match between Daniel Galan and the top-ranked Japanese player, Yoshihito Nishioka. It turned out that Saya had traveled to the UK with her mom to be Nishioka’s special guest at Wimbledon.

Fans were taken aback, expressing their disappointment and frustration online. The situation escalated to such an extent that Saya had to release a statement on Twitter to address the uproar.

[English Translation:

To all of my wonderful supporters

I wanted to share some personal news with you that you may have already seen in a few reports. I’m currently in a relationship with the professional tennis player Yoshito Nishioka. We both look forward to nurturing our bond and supporting each other in the days to come. Your continued warmth and encouragement would mean the world to us.]

For Western audiences, Saya having a boyfriend may seem trivial, but for her Japanese fans, it caused a 10% drop in Weather News Live’s stock and an immediate loss of thousands of followers. When she reappeared on screen after Wimbledon, the chat was overwhelmed with tennis ball and Nishioka-themed spam messages.

This situation may seem unfamiliar to those unaware of East Asian idol culture. In Japan, fans are less accepting of idols being in relationships, expecting them to remain single. While Saya isn’t technically an idol, Weather News Live owes much of its success to including attractive young women like her in their strategy.

The company holds annual auditions to find weather reporters who can entertain with their charm, subjecting them to intense scrutiny and limiting their personal freedom. This means women like 29-year-old Saya can’t make basic life decisions without triggering scandals.

The line between being a weather reporter and an idol is blurred for Saya. Despite the financial rewards, living under such public scrutiny takes a psychological toll. A woman having a boyfriend shouldn’t be headline news or a scandal. This raises the question: Why are these idols, including weather reporters, held to such strict standards?

What is idol culture?

First, it’s good to try and define what an idol actually is. The term “aidoru” (アイドル) is written in katakana. It comes from the English word “idol.” In Japan, it only gained popularity in the 1960s to refer to performers in a carefully curated group.

In 1962, Johnny Kitagawa founded Johnny & Associates and created Johnnys, Japan’s first idol group. He introduced the idol trainee system, where talents joined at a young age, training in singing, dancing, and acting until they were ready for their debut. The concept of idols gained prominence in Japan in November 1964 with the release of the 1963 French film “Cherchez l’idole” as “Aidoru o Sagase (アイドルを探せ).”

Throughout the 70s, idol culture took off with various TV shows and magazines advertising singing competitions. The 80s were known as the Golden Age of idols, with various idols making their debut. Baradoru (バラドル, variety show idols) increased in popularity rapidly with a variety of singing competitions.

It’s an understatement to say that the idol concept is popular; the sheer number of Japanese idol groups is staggering. For instance, Johnny’s Kinki Kids and Arashi, debuting in the 1990s, remain among the industry’s most enduringly popular acts. And if you’re not already familiar with Japan’s most famous girl group, you’ll undoubtedly recognize AKB48 from the countless ads and posters lining local streets.

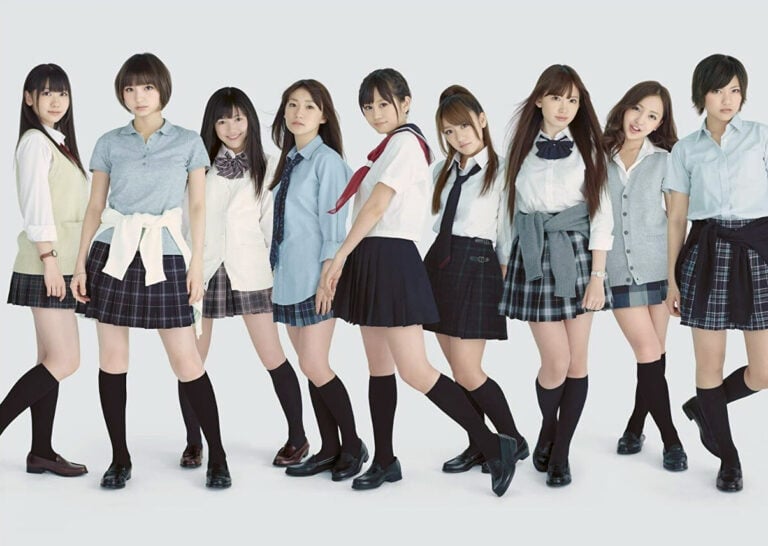

AKB48 (2010) popularized stylized school uniforms as costumes.

If you’ve watched videos of Japanese idols, you know their main role is singing and dancing on stage. That’s technically accurate, but it’s more complex than that, especially for underground idols, who often put in extra effort compared to mainstream ones.

When they join an idol recruitment company, they don’t immediately start singing and dancing – they’re not even considered idols yet. There’s extensive training involved, covering behavior and communication alongside singing and dancing. Some new talents are grouped together, which can be either a hit or a miss. Imagine having to work alongside someone you despise for your entire career, unlike a short-term group project.

Upon debut, their responsibilities extend beyond performing. They also need to market their new content, often through appearances on reality TV shows and handshake events. These events involve brief greetings, no photos or performances. Devoted fans, often known as otakus, go to great lengths to increase their chances of meeting their favorite idols.

What is the no-dating rule?

One of the more straightforward aspects of the job is singing and dancing, but the real challenge lies in adhering to a multitude of rules. While the specific rules may vary among recruitment companies, one common thread is a strict privacy policy. Idols are expected to maintain an image of being “perfectly imperfect” – relatable and down-to-earth rather than Prince Charming or Cinderella. To preserve this image, they are prohibited from publicly displaying relationships or engaging in any scandalous behavior.

Despite the continuous rise of idol culture, certain recurring issues persist. The most significant concern is the prevalence of assault and harassment, particularly but not exclusively targeting female idols. News reports about idols being stalked by obsessed fans seem distressingly frequent.

Member Taiko Sasaki was targeted by a 17-year-old high school student with a box cutter. Luckily, she was arrested before anyone could be hurt.

What’s even more concerning is that this culture of manufacturing female talents and thrusting them into the public eye often results in fan bases dominated by older men. While plenty of people casually enjoy idol culture as harmless fans the way you consume any media, J-pop doesn’t always target typical music enthusiasts.

In a way, it instead encourages the development of parasocial relationships with extreme fans. When an idol enters a romantic relationship, it diminishes her appeal and marketability. Her talent represents only a fraction of the overall fantasy woven around idols.

An example of one of these scandals comes from the most significant scandal stemming from the no-dating culture that occurred in 2012 when a tabloid magazine reported that the renowned AKB-48 member, Minegishi Minami, had spent the night at a man’s house.

The severe backlash led to Minegishi’s immediate demotion to trainee status within the group. Within 24 hours, she was pressured to shave her head as a symbol of penance and apologized on the official AKB-48 YouTube channel. This incident garnered headlines both in Japan and the Western world.

Minegishi Minami in 2023

This is one of several instances of no-dating scandals involving female idols, with male idols facing similar situations. For instance, when heartthrob Kuyama Masaharu announced his marriage in 2015, his talent agency, Amuse, saw its stock price drop by nine percent.

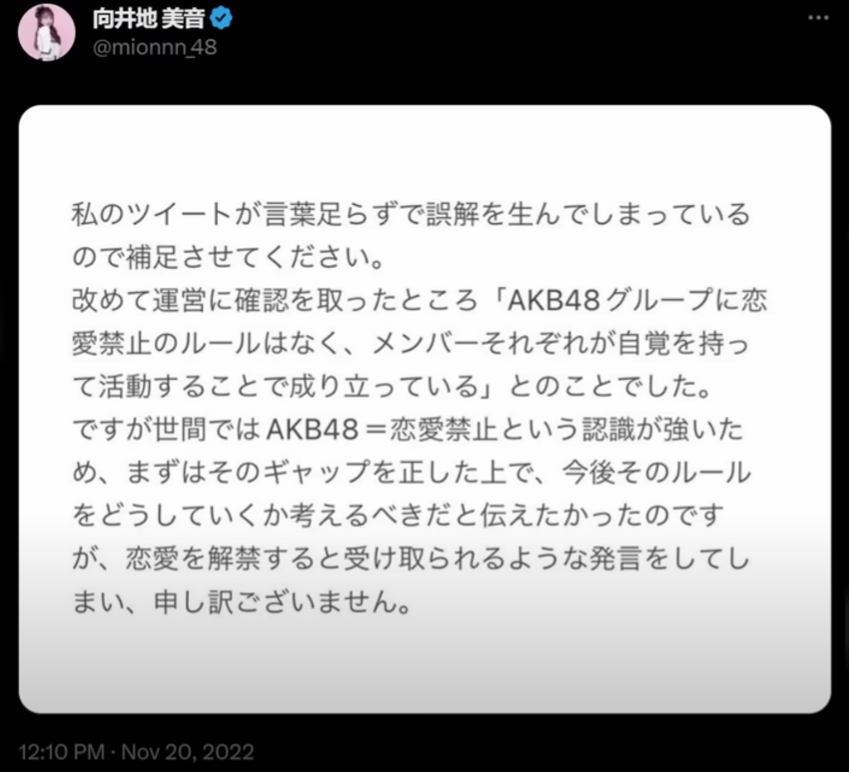

Although it may seem outdated, the no-dating culture is enduring, even when a rule isn’t explicitly stated, like Minegishi’s case. As recently as last year (in 2022), during another AKB-48 no-dating scandal, the group’s director, Mukaichi Mion, who was a former idol herself, made a sympathetic statement on Twitter. She suggested it might be time to reconsider the no-dating rule and mentioned she would discuss it with management.

However, the backlash to Mion’s statement was so intense that she felt compelled to issue another statement the following morning, clarifying that she misspoke. According to her, after consulting with management, there was, in fact, no official no-dating rule, and the group’s members were free to make their own dating decisions.

[English Translation:

Please allow me to clarify because my tweet lacked detail and led to misunderstandings. Upon confirming with the management again, it was conveyed that ‘there is no rule against romantic relationships in the AKB48 Group, and each member conducts themselves with self-awareness.’ However, there is a strong perception in society that AKB48 prohibits romantic relationships. Therefore, we should first correct this gap in perception and then consider how to proceed with this rule in the future. Unfortunately, my statement may have been interpreted as advocating for lifting the ban on romantic relationships; for that, I apologize.]

Idols are expected to cultivate fantasy relationships. Fans connect with the idol’s character through merchandise, developing a relationship with the persona they embody. Idols typically conceal their true selves, which is why anything they do that tarnishes the persona of the idol can face severe backlash.

What are parasocial relationships?

These forms of relationships between idols and fans are often a form of parasocial relationships, which, taken to an extreme form, can become very toxic and dangerous, as you can see.

A parasocial relationship is a one-sided relationship where one side extends emotional energy, interest, and time while the other party remains unaware of their existence. It is common for these relationships to be aimed towards famous celebrities such as idols, given the widespread public persona and incentive to interact and engage with fans.

The term “parasocial relationships” was coined in a 1956 article by two researchers who observed emerging connections between audiences and the stars of news programs, television shows, and movies. Today, parasocial relationships may appear particularly intimate due to the ease with which celebrities can interact with their followers on social media. However, these interactions often lack the depth and meaningfulness found in our relationships with real-life friends and family.

Group of idols performing in Osaka

Parasocial relationships are typically commonplace and entirely normal. In fact, the emotions we experience within these relationships can be just as powerful as those in other types of connections. Media is a convenient means of fulfilling our social needs, offering a low-barrier entry point.

Moreover, these interactions can create safe spaces for individuals with social anxiety, boosting their confidence and making real-world interactions feel safer. Additionally, they can aid in identity development by providing role models. In essence, parasocial relationships offer a way to practice social interactions, particularly through engagement on social media, facilitating social learning that can be applied in real-life situations.

However, a parasocial relationship can become unhealthy if it starts to resemble stalking behavior. And this is true when looking at extreme fans who start causing direct or indirect harm to their beloved idols.

While certain aspects of a real person may influence the idol’s image, the core essence remains rooted in fantasy. When this illusion is shattered due to aging or being seen on a date, the idol’s marketability diminishes, potentially jeopardizing their career, reputation, and even safety.

The allure of idols is similar to when fans get attached to a character from fictional media like anime, movies, books, etc. An idol, too, is essentially a fictional character, often depicted as pure and available. However, most fictional characters in anime and movies are exactly that, fictional. It is easier to detach from reality since they are the creation of artists. Idols, on the other hand, are real people recruited during their teenage years and bound by contracts.

Links:

声優を目指した異色のキャスター・檜山沙耶のあふれる漫画&アニメ愛 (The Unique Caster Saya Hiyama, Who Aspired to Become a Voice Actor, Overflows with Manga and Anime Love) https://wanibooks-newscrunch.com/articles/-/2452

「弱者男性の姫」お天気キャスターの熱愛宣言に飛ぶ誹謗中傷! ファン激怒の背景に“アイドル営業の側面 (Princess of Vulnerable Men’ – Weathercaster’s Declaration of Love Sparks Defamatory Attacks! The Furious Fans and the Underlying ‘Idol Business’ Aspect) https://news.yahoo.co.jp/articles/ec65b886f8d560121d0c83a0e585aed736aae9cc

“Arashi for Dream” : Idol—fan relationships in Japan by Lampione Gombas https://www.utupub.fi/handle/10024/152508

Parasocial Interactions: JKT48 Fans in Forming Relations with Idols and Social Environment by Siti Ntara Muthmainah Mulya and Ahmad Mulyana https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4216044

Japan’s Ridiculous Weatherwoman Fiasco by Japanalysis https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z7QG9owYEUY