Anyone who has spent notable amount of time in Japanese spaces will know Japanese communication styles can be quite different from what they’re use to. For example, I remember a conversation I once had with a Japanese friend. We discussed going out to dinner that weekend and even set a time and date, but what I didn’t realize at the time was the weight of the word “maybe” when my friend said, “maybe I’ll be free”. When Saturday came around and I sat at the train station alone, I learned an important lesson that “maybe” means “no”.

What is “Honorific Language”?

Learning how to communicate in Japan roots in understand the mindset of Japanese culture. Of course, there are so nuances to go over that I could write a book alone on the topic, but one for now the only aspect I would like to explain is the use of honorific language in Japanese. In short, honorific language is the method of showing respect when speaking.

I have heard many people studying Japanese claim honorific speech is too complicated and they will never bother to learn it, but I think this is a bad mindset to have if you wish to live for an extended period of time in a Japanese community. By never learning how to use honorific speech, you are adding an additional artificial barrier in communication between you and the average Japanese person. This will hinder your ability to foster long term interpersonal relationships and limit the ways you can show gratitude towards those who show you kindness in Japan.

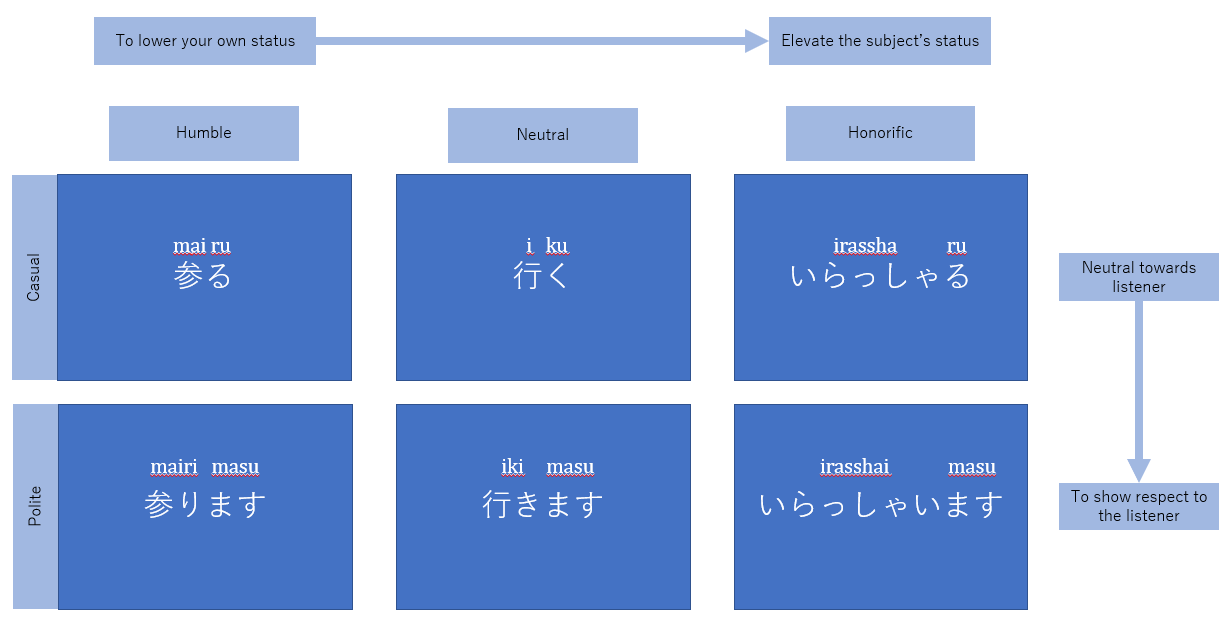

It is quite a complex system with many layers, but if you understand honorific speech, you first have to understand its two primary dimensions: showing respect to the person you are speaking to and showing respect to the person you are speaking about.

Looking at that chart above, you might feel immediately overwhelmed, but don’t panic! Even to Japanese people it’s complicated! You are not alone in thinking it’s confusing, but I will explain more later.

While you may not need to be a perfect master of honorific speech, understanding how it works and why it is used is very beneficial because it allows you to show a Japanese people that you do care to be respectful of their culture and will make every day interactions as well as both business and interpersonal relationships much easier to navigate.

Why do Japanese use “Honorific Language”?

Honorific language has a long history imbedded in hierarchal power dynamics, but to help understand the use of honorific language in the modern day, we should first consider differences in underlying mindsets in a conversation between America (and many European cultures) and Japan. For Americans, when we talk to one another, you may find a large element of our communication is to establish a closer relationship with one another.

Say you meet Danny in your Friday afternoon Japanese class at the community center, and you start to banter back and forth about your frustrations with Japanese conjugation. Here, the only purpose of this communication is creating a connection between the shared feelings of you and Danny. Then when class ends and you are walking out the door, it isn’t awkward to ask Danny if he wants to go out for drinks.

Of course, Japanese people also like to get to know each other and become friends like anyone else, but there’s a layer in their communication that we English speakers rarely worry too deeply about: respect. In Japanese conversation, it’s important to communicate to those around you that you respect their position and life, often denoted by age. To communicate naturally in Japan, one important thing you have to mind is the power differentials between people.

To us Americans, we tend to dislike enforcing power differentials. This in part comes from the fact that America is a nation of immigrants (not only with modern immigration but also in America’s foundation). When you have so many cultures at once, you must learn to communicate and share our thoughts with one another because of a lack in foundational culture to fall back on. Even in modern day when an idea of “Americanism” has is established, we still have a variety of diversity and a culture that grew out of this diverse setting which makes it more difficult to default to a singular norm. This creates a pressure to get to know one another to establish the boundaries of communication that a long history of shared cultural norms could provide.

Conversely, Japan is a fairly small and largely monolithic country with much less diversity within their cultural make up and foundation. This leads to a singular culture that informs the way they communicate and interact with one another.

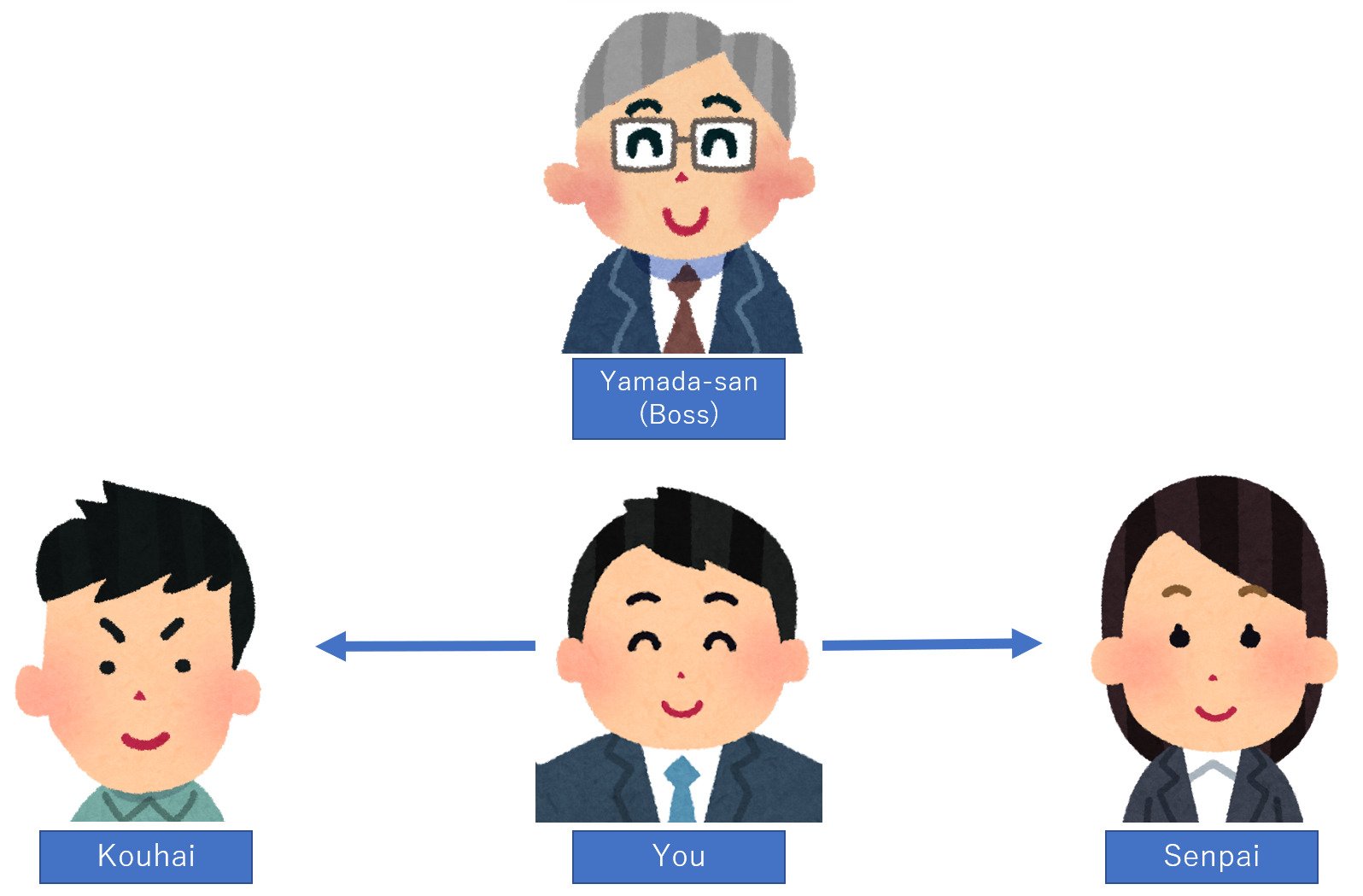

One of these cultural norms that you’ve likely heard of is the “senpai/kohai” culture. Starting in high school, most Japanese people learn the structure of senpai (the higher up students or workers) who teach and guide the kohai (the younger and thus less experienced student/worker). In turn the kohai shows gratitude for the guidance their senpai can provide them. This mindset pervades to other parts in life as you learn to show respect as a way to show gratitude to those who can provide the wisdom you lack.

On a social level, you can think of it as someone is always above and someone is always below. This isn’t good or bad, it simply is. At work there is always a manager and above them a senior manager. At school there are always students further along in the program than others. The benefit is within this hierarchy, you can learn to find your identity and that identity becomes a part of your status in society. The purpose of honorifics is to communicate this status in a way that makes it clear where you stand with one another and to communicate your appreciation for what others can do for you or what you have done for others.

So, to us it may seem confusing to speak to your friend who is maybe only five or ten years older than you in a respectful manner, but in Japanese you’re not just being uptight and formal with your older friend. The purpose of the honorific system is a method of communicating to your older friend that you appreciate what they have to offer you. Your senpai helps you and in turn when you become the senpai you will do the same and guide your younger colleagues.

In a sense, you can think that in communicating, your goal is to communicate how you relate to one another and while you are working and living in Japan, you learn to communicate your gratitude towards others.

How do I use “Honorific Speech”?

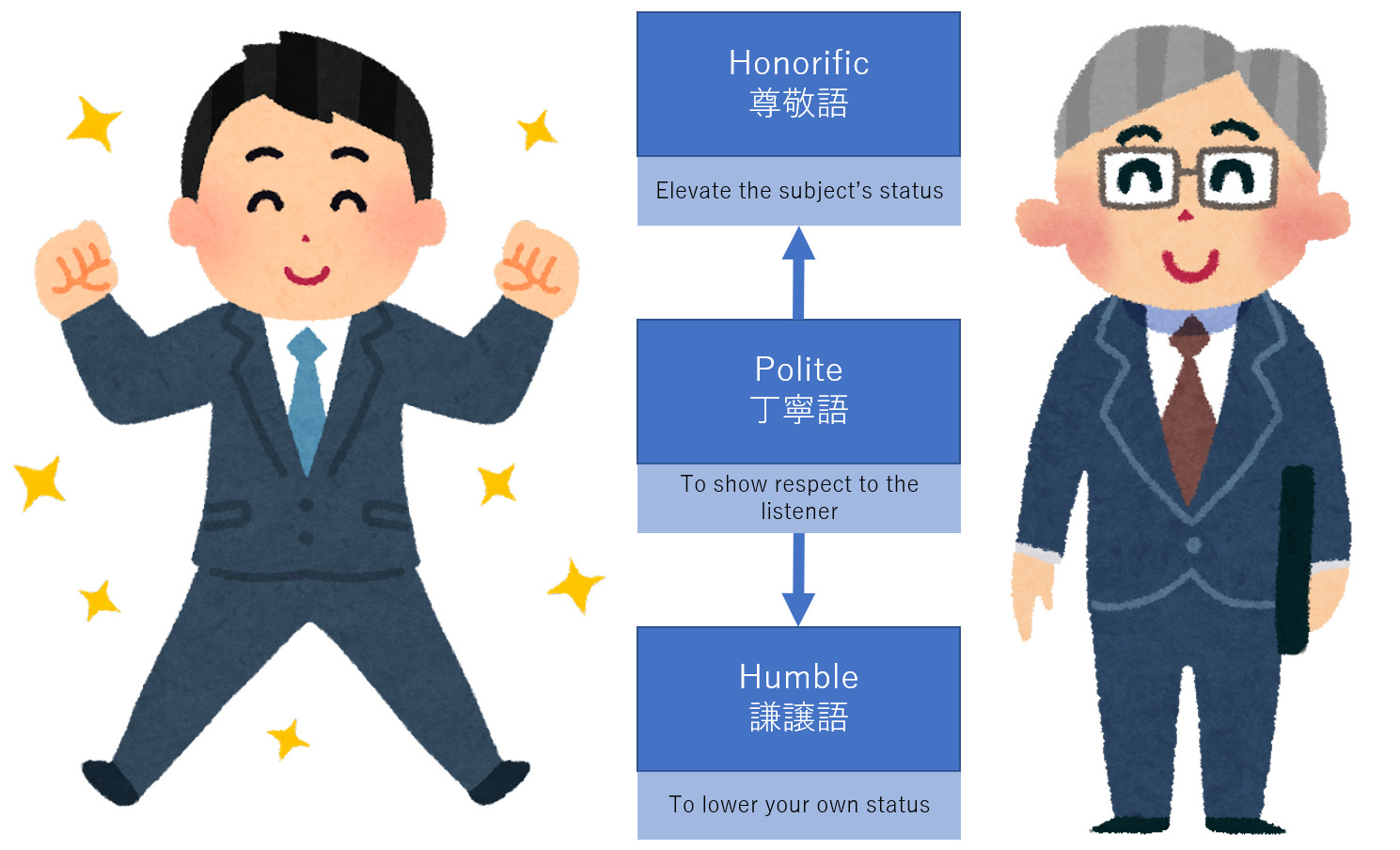

As mentioned before, honorific speech has two primary dimensions: showing respect to the person you are speaking to and showing respect to who you are speaking about.

So to start you have your standard casual speech (行く/iku, 行った/itta, 行っている/itteiru, etc.). This level of speech is used in casual situations such as when talking with your friends or your kohai. When you wish to show respect to the person you are speaking to, you will switch into polite speech called teinego or 丁寧語 (行きます/ikimasu, 行きました/ikimashita, 行っています/itteimashita, etc.). Say I am talking to my senpai or my boss, it is good for me to speak to him politely using this form.

Then you have what is called sonkeigo or 尊敬語 which is honorific form and kennjougo or 謙譲語 which is humble form. The purpose of honorific form is to elevate the status of your subject you are speaking about while the purpose of humble form is to lower the status of your subject (typically lowering your own status). This part is more complicated than the polite form and tends to be the part of honorific speech people struggle with the most.

To understand how these different forms are used, let’s take the following diagram. Say you’re at work and your team needs to finish a project by the end of the week. Tanaka-san (your kohai) is tasked with writing a code, but he runs into an error he doesn’t understand. While talking, he will speak to you politely (using teinego) to show respect while you tend to speak to him casually as you’ve worked with each other for several years and there’s no need to be formal. The two of you are confused and unable to solve his issue so you go to Saito-san (your senpai) to ask her for help. She’s very smart and can help you both, so you both speak to her respectfully.

Now the code is done thanks to Saito-san, so your project gets done and you now need to email Yamada-san, your boss, and let him know you’ve finished the project on time. Here, like your senpai, you need to be polite, but now the status of your boss is important so you will use honorific form when referring to Yamada-san to elevate his status and humble form when referring to yourself to lower your status in relation to his status.

This honorific and humble form is typically most necessary in emails, but you will see it in many places in Japan regardless whether you work at a formal company or not. For example, when you walk into stores often workers use this honorific form to show respect to their customers as it has become imbedded in the service culture of Japan. At times when one friend can help another friend with something important, they can also use this honorific form as a way to deeply express gratitude. In fact, you may have learned before eating to say “いただきます” (itadakimasu). This phrase actually comes from “いただく” which is the humble form of “食べる” (taberu/to eat).

So, in summary, you can understand these levels of speaking not as levels of formalities, but ways of showing respectful gratitude.

Tips to help you be more respectful

One seemingly simple but very effective way to be respectful is just to learn the simple phrase “すみません” (sumimasen). This phrase is often translated to “excuse me”, but it has many meanings. You can say すみません anytime you want to say “I’m sorry”, “pardon me”, or “thank you”. For example, if you are at a restaurant and want to call a waiter over, you’d call out “すみません” to get the waiter’s attention. Then when the waiter comes over they will say “すみません” to a way to acknowledge your wait for them. Then say you want chopsticks, so you ask them and as they hand you chopsticks, you accidentally drop them and quickly apologize by saying, “すみません” to acknowledge the inconvenience you’ve caused them. They wave it off with a smile and hand you a second set of chopsticks and again you can say “すみません” to thank them for the trouble they went through to help you.

This phrase essentially acts as an acknowledgment of another person. If you don’t know how to say a lot of things in Japanese, by being able to say “すみません” you quickly communicate respect to the person you are interacting with making even simple things like asking for directions or when someone scoots over on the train to make space much smoother.

A second tip is to simply ask what the right thing is to do. Say you have been going out with a guy and it’s the third or fourth date, but you are both still speaking politely. It can be hard to know when you can or can’t switch between formalities. Sometimes people are very laid back and you know quickly it’s ok, but with other’s it may be less clear. If you want to be casual with that guy you’ve been dating and really like, you can just ask them if it’s ok to speak informally. Most of the time they are also struggling with the same question and by simply asking makes both of you feel less stressed.

Same with at your job, if you don’t like talking politely when you go out for drinks after work, you can simply ask your senpai or coworkers if it’s fine for you to be informal. For most Japanese people, they understand these rules are not the same in English as it is in Japanese (as almost all Japanese people have had at least basic English grammar even when they don’t speak English well), so they understand that it may be difficult for you. So simply tell them so and it can avoid any misunderstandings.

My third tip is to not hesitate to ask Japanese friends or coworkers for help. Say you need to send an email to a client and you’re still unsure after three or four hours of stressing about whether you sound respectful enough. In this situation, you can always just ask someone for help. I have this experience so often as I email professors or researchers from outside my lab. In fact, it stresses me out so much that there have been times my senpai has walked past my desk and just started laughing because he knew I was writing in honorific speech just by the look on my face.

However, if you live in Japan, you have a great benefit: you are surrounded by Japanese people! Use this to your advantage and ask them for help! If you’re not in Japan, there are also websites (such as hinative) where you can ask natives to proofread your writings and give advice.

Likewise, if you are worried about how you can communicate or when you should be polite or informal, you can ask your friends and coworkers for their opinion. Not only will this help you learn to navigate these situations more efficiently than any class could, but it also helps you become better friends with those around you as now they know you care about Japanese and will feel more comfortable to ask you for advice when interacting with other foreigners or speaking in English.

The final tip is to not worry too much. If you make a mistake, it is ok. You are showing respect and gratitude just by trying and that is enough. While it’s always good to improve and become better in Japanese, the best way to do this is to try and make mistakes that you can learn from. So just do your best and be as polite as you can!