The restaurant hummed with cheerful voices and playful banter. Although quiet, you could hear the hum of joy from those sitting at the counter. White pieces of paper, each adorned with the names of different dishes carefully written with black ink, covered the walls.

Tables were filled with clusters of friends and coworkers, their spirits high as they shared drinks and stories on a Friday night. Amidst the excitement, the chef glided the sushi slices across the counter, and a small bottle of Nihonshu found its place between me and my friend. He poured the liquid into my cup before his own, and we clinked our glasses, sharing smiles and anticipation.

As the Nihonshu touched my lips, a gentle heat enveloped my senses, accompanied by a profound umami flavor. Delicate sweetness followed, dancing over my tongue, almost tasting oddly fruity beneath the robust facade. My friend had warned me not to wear perfume to the sushi shop, and at that moment, I understood why. The subtle complexity of the Nihonshu, blending harmoniously with the flavors of the fish, perfume would have overtaken all these little flavors I had never noticed before.

And so, it was at that moment I fell head over heels for Nihonshu. But what exactly is this intriguing drink? The name itself, “Japanese Wine,” speaks to its origins and heritage in Japan throughout history.

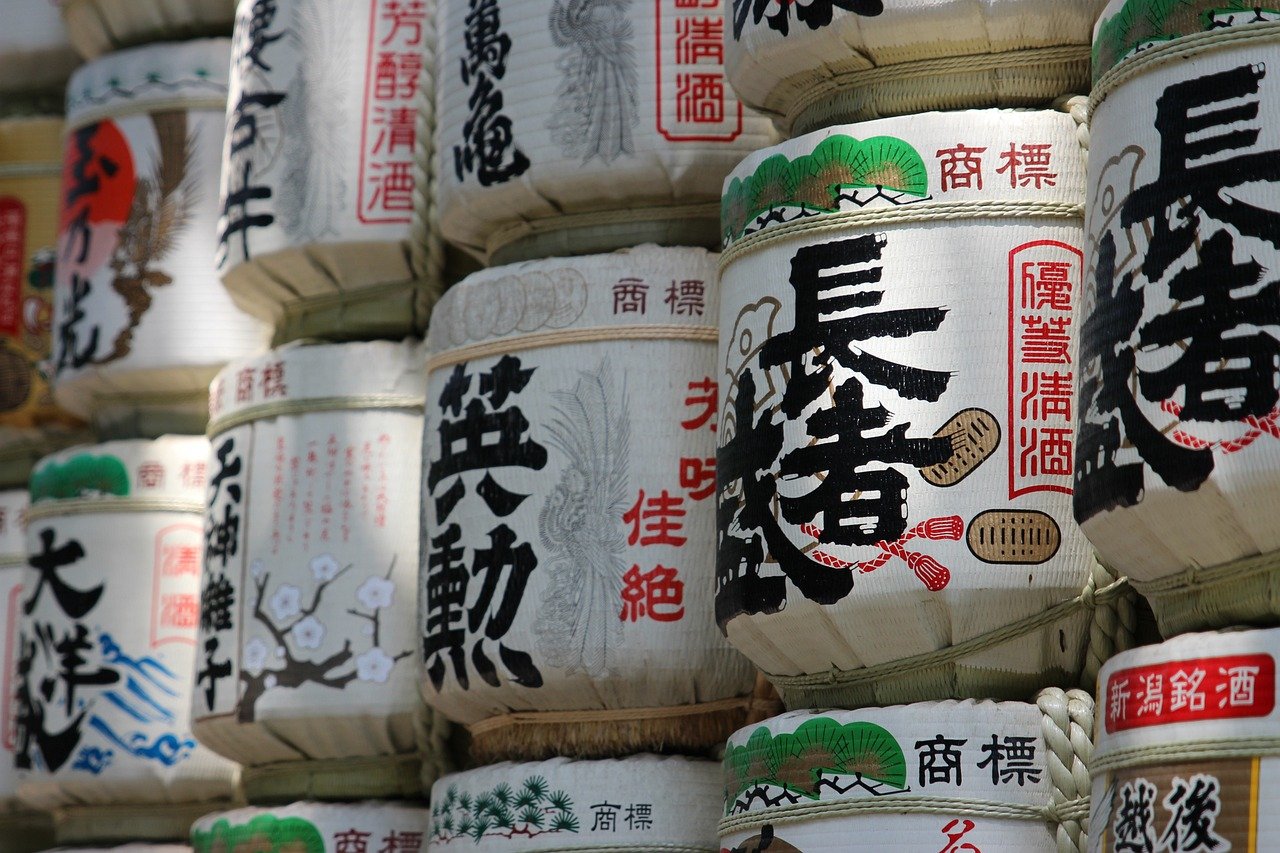

Crafted from rice, Nihonshu comes in a myriad of types and flavors, each offering a unique experience. Sadly, it seems that its popularity has waned in the face of Western-style liquors. Nevertheless, in the following article, I will delve into the diverse world of Nihonshu, and its production methods and encourage you to (safely) try this traditional style liquor.

What are the different types of Nihonshu?

Nihonshu, also known as Japanese rice wine, offers a delightful diversity of types and styles, each with its own distinct characteristics and flavors. These distinctions stem from variations in ingredients, brewing methods, and regions of production. Let’s explore some of the main types of Nihonshu:

One of the traditional types is Junmai (純米) sake, made solely from rice, water, koji mold, and yeast. It refrains from using any added alcohol or other additives, resulting in a rich, full-bodied flavor with a prominent rice taste.

On the other hand, we have Honjozo (本醸造) sake, which involves the addition of a small amount of alcohol to the mixture of rice, water, koji mold, and yeast. This addition enhances the aroma and contributes to a crisper and drier taste compared to Junmai sake.

Ginjo (吟醸) sake stands out as a premium variety made with rice that has been polished to at least 60% of its original size. This style can be produced in Junmai or Honjozo versions. The slower fermentation and lower temperatures during brewing bring out more delicate and fruity flavors, resulting in an aromatic and refined Ginjo sake. Currently, despite an overall decline in sake consumption in Japan, there is a notable increase in the consumption of ginjo grade sakes.

While the ginjo category offers delightful sakes, when it comes to special occasions, it’s alternative, Daiginjo, is even more elegant. Daiginjo, meaning “big ginjo,” is often the most esteemed product of a sake brewery, showcasing the pinnacle of the brew master’s skill. To qualify as daiginjo, a minimum of 50% of the outer rice layers must be meticulously polished away.

Given that breweries employ their finest rice with the highest polishing rate for Daiginjo, extra care is also taken in other production aspects. Daiginjos are often brewed in smaller tanks compared to Junmais and Ginjos, ensuring better control over fermentation temperature and speed. The production of koji, a crucial element in sake brewing, is also carried out with great precision; some breweries even have a dedicated room solely for making daiginjo koji.

Nigori (濁り) sake is a cloudy or unfiltered type of Nihonshu. Some rice sediment is retained through coarse filtration, lending a cloudy appearance and a sweeter, creamier texture compared to other types of sake. If you’re looking for an everyday drinking sake, Futsushu (普通酒) is a basic and affordable option. It may contain a higher alcohol content due to the addition of brewer’s alcohol, but it is versatile and can be enjoyed both warmed and chilled.

For those seeking unique flavors, Taru (樽) sake is aged in wooden barrels, often made from cedar. The wood imparts a distinct woody aroma and a refreshing, crisp taste to the sake. And lastly, Koshu (古酒) sake is aged for an extended period, ranging from several years to several decades. This aging process adds complexity, deepens the flavor, and often produces a golden-colored, mellow, smooth Nihonshu.

What is the history of Nihonshu?

The history of Nihonshu, commonly known as 日本酒 or Japanese rice wine, is a fascinating journey that dates back over a millennium. The roots of Japan’s use of koji mold for starch conversion and practicing shaped by cultural, technological, and social developments throughout the centuries.

During the Yayoi period, around the 3rd century, the Japanese began making a crude form of fermented rice beverage, which laid the groundwork for what would later become Nihonshu. In the 7th and 8th centuries, during the Asuka and Nara periods, Japan imported advanced brewing techniques from China and the Korean Peninsula, significantly influencing the development of Nihonshu production.

The Three Sake Tasters from an engraving after Okumura Masanobu (1710)

By the Heian period (794-1185), sake brewing had become a significant industry in Japan. Sake served not only as a drink for festive occasions but also as an important offering in religious rituals and ceremonies. The Kamakura period (1185-1333) saw temples and shrines play a crucial role in sake brewing due to their vast rice fields and resources.

Advancements in sake brewing techniques occurred during the Muromachi period (1336-1573), including using koji mold for starch conversion and practicing multiple parallel fermentation. From the 16th century onwards, sake began to be traded as a commodity, leading to increased commercialization and standardization of production methods.

During the Edo period (1603-1868), sake became more accessible to the general public, resulting in regional variations in taste and production methods. The government also introduced regulations and quality control measures to maintain the reputation of sake. The Meiji period (1868-1912) brought significant changes to sake production with industrialization and the introduction of pasteurization techniques, stabilizing and improving the quality of sake.

In the 20th century, the sake industry faced challenges such as competition from other alcoholic beverages and a declining domestic market. However, efforts from the Japanese government and sake breweries led to a revival of interest in Nihonshu both domestically and internationally.

How is Nihonshu made?

Nihonshu undergoes a meticulous and intricate brewing process comprising several key steps. The traditional method of Nihonshu production demands careful attention to detail and precision.

To begin, high-quality rice is selected as the foundation for exceptional Nihonshu. The outer layers of the rice grains, which contain proteins, fats, and impurities that could negatively impact the sake’s flavor, are removed through a process called polishing or milling. The degree of rice polishing determines the type of Nihonshu produced, such as Ginjo or Daiginjo.

Following the rice polishing, the grains are thoroughly washed to eliminate any remaining bran and impurities. Subsequently, the rice is soaked in water to ensure gradual and even hydration. Proper soaking facilitates efficient starch conversion during the subsequent steps. The production of koji, a crucial element in Nihonshu, comes next.

Steamed rice is spread out in a dedicated room and inoculated with a mold known as Aspergillus oryzae (koji-kin). This koji mold breaks down the rice starch into fermentable sugars through a process called saccharification. Koji production is an art that requires expertise and precise control of temperature and humidity.

The next phase involves creating a small batch of Moto, a starter mash. The Moto is made by combining the prepared koji, steamed rice, water, and yeast in specific proportions. This Moto is then incubated for several days, during which the yeast converts the sugars into alcohol.

Making sake koji (Okuhida Sake Brewery)

After the Moto is ready, it is combined with larger quantities of steamed rice, koji, and water to create the main mash, also known as Moromi. The Moromi undergoes fermentation over several weeks, with yeast continuously converting rice sugars into alcohol. The fermentation process significantly influences the sake’s flavor profile.

The post-fermentation phase transforms the beverage into what appears to be a tank filled with rice porridge. Nevertheless, the process of separating liquid from solid remnants has various techniques.

The assakuki, resembling an accordion-like apparatus, is the most commonly employed technique. The process entails placing the sake within mesh bags nestled within the folds of the “accordion.” By compressing these bags, the liquid finds its way through a pipe situated at one end of the contraption. The result is an energetic and efficient method yielding a significant quantity of sake.

On the other hand, for those seeking a more delicate approach, the funashibori is a second technique. Embracing gracefulness, this method involves arranging the sake in mesh bags and gently housing them inside a long box aptly named the “fune” for its boat-like shape. Applying pressure to the lid releases the sake, minimizing flavors derived from the lees – the rice and yeast sediment left behind. Although this process yields a smaller quantity compared to the assakuki, but what it produces tends to be higher quality.

For the most discerning palates, an exclusive technique known as shizuku occasionally finds its place in the sake-making process. Derived from the Japanese word for “droplets,” shizuku encompasses a “free run” pressing, or in some cases, no pressing at all. The sake is ensconced within mesh bags suspended from poles within tanks. As nature takes its course, only the liquid that naturally drips out is collected and bottled. The outcome is a seamless sake, albeit often accompanied by a higher price point.

The sake then undergoes filtration to remove any remaining impurities and is pasteurized to stabilize it and prevent further fermentation. In the case of premium sakes, multiple pasteurization steps may be employed to achieve a smoother taste.

Depending on the type of sake, it may undergo a period of maturation to develop more complex flavors. Aging is particularly common in Koshu sake. Before bottling, the sake is often diluted with water to achieve the desired alcohol content. It is then carefully bottled and labeled for distribution and consumption.

How is Nihonshu drunk in Japan?

When selecting Nihonshu, consider the wide variety available, each boasting distinct flavor profiles and characteristics. Exploring different styles, such as Junmai, Ginjo, or Daiginjo, can help you find the sake that best suits your taste preferences.

Another thing to consider is that the temperature of the Nihonshu significantly impacts its taste. You can enjoy it chilled (Reishu) by keeping the sake in the refrigerator or slightly chilled (Hiya) by letting it sit at room temperature briefly. For a lukewarm (Nurukan) experience, warm the sake to around body temperature, while for a hot (Atsukan) sake, warm it to a higher temperature. Some sakes, like Futsushu and Nigori, are often enjoyed hot.

Using appropriate vessels can also add to the experience. Traditional Nihonshu is served in small ceramic or glass cups known as “ochoko” or “guinomi.” For special occasions or premium sake, a small ceramic or glass decanter called “tokkuri” is used to heat the sake before pouring it into individual cups.

There is a certain etiquette to follow when pouring and receiving sake. When someone pours sake for you, hold your cup with both hands as a sign of respect and gratitude. Similarly, when pouring for others, use both hands as well. It is polite to pour for others before refilling your own cup.

Nihonshu is meant to be sipped and savored slowly, not consumed hastily. Take your time to appreciate the aroma and flavors of the sake. In Japan, it is customary to say “Kanpai” (乾杯) before drinking, which is the equivalent of saying “Cheers.”

This delightful beverage pairs exceptionally well with a wide variety of dishes. In Japan, it is common to enjoy sake with traditional foods like sushi, sashimi, tempura, and grilled fish. The subtle flavors of sake complement and enhance the taste of the food.

Don’t hesitate to experiment with different types of sake, serving temperatures, and food pairings. Nihonshu offers a diverse and nuanced drinking experience, making exploring its various facets a delightful journey. Remember, responsible drinking is essential, and moderation should always be exercised. Enjoy the pleasure of drinking Nihonshu in a social and convivial setting while appreciating this beloved traditional Japanese beverage’s rich cultural heritage and craftsmanship.