Are you an anime enthusiast? A dedicated gamer, perhaps? Or maybe you have a unique passion, like for the ancient game of shogi or into very specific bands. Nowadays, having a favorite anime series or video game is pretty common. But did you know that the love for anime, at one point, wasn’t as widely accepted as it is today, especially in Japan?

You might have encountered the term “otaku” before, or it could be entirely new to you. In the Japanese context, “otaku” typically refers to individuals with a deep-seated passion for specific content, such as manga, anime, or idol groups, well into their adult years. They’re often seen as “superfans,” but this label can also come with stereotypes of social awkwardness.

For the younger generation nowadays, “otaku activities” (ヲタク活動) are commonplace, but how did otaku, once associated with a negative image, gain “citizenship” into mainstream culture? In this article, we’ll delve into the concept of “otaku,” exploring how it has evolved in modern times and how its perception and usage differ between Japan and the rest of the world.

Where did the image of otaku come from?

The word “otaku” (オタク) comes from the second-person pronoun “otaku” (お宅), which generally is a polite form of addressing others in Japanese. There grew a custom of using this term within fan communities, striking early writers such as Akio Nakamori as odd.

“…we got as far as naming the hordes of gloomy, obsessive boys you see everywhere these days as “otaku.” I think most of you can figure out the origins of the word, but it’s like this: don’t you think it’s a little creepy to see junior high school kids addressing each other with “otaku” at manga and anime conventions?”

(“Can Otaku Love Like Normal People?” by Akio Nakamori, 1983 (Translated with permission by Matt Alt))

In these articles by Nakamori, we can see a stereotypical image of an otaku:

“The boys were all either skin and bones as if borderline malnourished, or squealing piggies with faces so chubby the arms of their silver-plated eyeglasses were in danger of disappearing into the sides of their brow; all of the girls sported bobbed hair and most were overweight, their tubby, tree-like legs stuffed into long white socks.”

(“This City is Full of Otaku” by Akio Nakamori, 1983 (Translated with permission by Matt Alt))

As you can see from the outset, the term carried a highly negative connotation. Primarily among those involved in the subculture, using “otaku” was a way of self-deprecation. However, as it gained traction among people outside the subculture, it quickly transformed into a means of exclusion for individuals who harbored deep passions for specific media and did not conform to societal norms.

Nevertheless, its negative connotations intensified following a gruesome serial killing case in the late 1980s. Between 1988 and 1989, Tsutomu Miyazaki started abducting and murdering young girls aged four to seven. His exceptionally graphic and horrifying crimes led to his death penalty sentence.

However, when the news media covered his case, they dubbed him the “Otaku Murderer” because of his extensive collection of pornography and horror films. While this portrayal misrepresented the concept of “otaku,” it triggered a widespread moral panic against otakus in Japan as a whole.

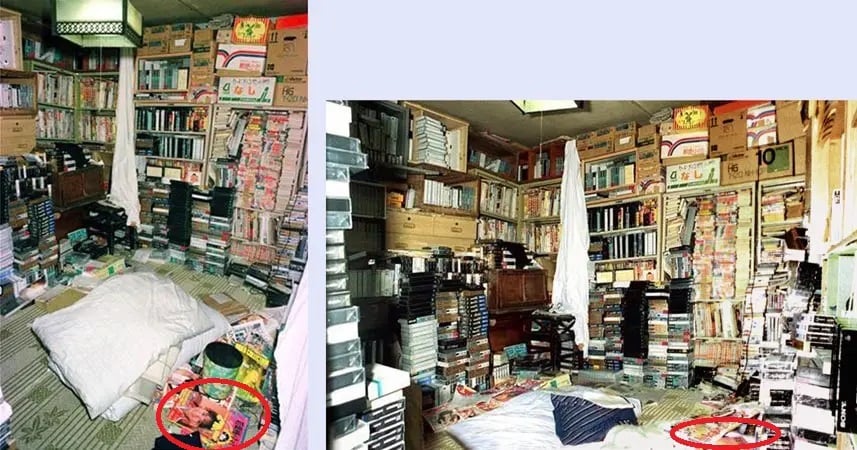

Photos taken of Miyazaki’s room and publicized to the Japanese media

The fact that Miyazaki filmed a young girl with a video camera after she was murdered and had it hidden in his vast collection of explicit and horror videotapes led to the belief that otaku blurred the line between reality and fantasy and that their lack of a clear sense of normality led to committing crimes.

This incident sparked the “Toxic Comics Riot,” which increased the tendency to believe that anime, manga, and video games have a negative impact on youth, and led to discussions in the mass media and PTAs. The “serial abduction of young girls” case spearheaded the criticism of growing pop culture in these discussions.

This incident solidified the perception that “otaku” equated to being a pervert or even a potential criminal, leading to the widespread acceptance of “otaku” as something very sinister and negative. Even NHK prohibited using the word “otaku,” deeming it a derogatory term. For example, Toshio Okada, a self-proclaimed otaku, wrote:

“I first learned of this fact when I was interviewed by NHK. As a self-proclaimed “otaku king,” I was asked to talk about the anime situation overseas. I was told that I could not use the word “otaku” in that context. I think NHK probably wanted me to use “fan” or “mania” instead.”

(“Introduction to Otaku” by Toshio Okada, 1996)

How have things changed?

While in the 1980s, otaku were often viewed as eccentric, as time progressed into the ’90s, they began to be seen as potentially dangerous eccentrics. However, people were still avidly consuming media like anime and video games. Most otakus were not dangerous criminals but enthusiastic fans of the shows and books they loved.

So, what brought about this transformation into the modern day, where watching anime is normalized in Japan? The answer is quite straightforward. Money.

In 1995, a new anime was introduced: Neon Genesis Evangelion. This anime was created by otaku, for otaku. While it wasn’t the first of its kind, it was among the first to hit mainstream. Evangelion marked a significant turning point from anime produced for mass audiences to anime tailored for anime enthusiasts.

The series was released during a bleak period in Japanese history, known as the “lost decades” following the economic bubble burst. Many young people had lost faith in their system, and the hopelessness and despair of Evangelion’s main character resonated with them. The anime became a major sensation, dominating the 90s. Evangelion’s popularity served as a beacon of hope for otaku, and as people identified with its characters, they began to embrace the “otaku” label more openly.

This triggered a shift in anime. Until then, anime had primarily centered around giant robot characters or promoting the anime itself, such as through original video animations (OVAs). But Evangelion elevated the characters themselves, resulting in a plethora of secondary artwork and promotional materials featuring the (albeit fetishized) portrayal of women from the anime. This catered to the desires of otaku and led to immense financial success for the franchise. This shift changed the perception of otaku, as they began to achieve domestic and international financial success.

Shortly after Evangelion’s success, Pokémon was released. The franchise’s creator proudly identified as an otaku, openly admitting his dedication to every aspect of Pokémon, from collecting bugs to designing monsters. Pokémon became a global phenomenon, pushing Japan into its own cultural empire. This unprecedented financial and cultural success forced Japanese society to acknowledge the otaku phenomenon. As the younger generation grew up with products like Pokémon in the mainstream, the concept of being an otaku no longer carried the same stigma as before; it became normalized.

In the early 2000s, the “Train Man” series was released, based on a story about a lonely otaku on Ni-chan (an online forum popular in otaku circles) who falls in love and gets married. Additionally, around this time, celebrities who at first glance did not look like otaku, such as Shoko Nakagawa (TV personality) and Kendo Kobayashi (comedian), began to talk about anime, which had been considered otaku-like, in a funny but serious way on TV programs.

People who had never heard of the anime they introduced discovered how interesting it was, and many people gradually became less reluctant to watch “deep anime” as a result. In 2005, the word “moe” (萌え~ or slang for a term that refers to feelings of strong affection mainly towards characters from anime or related media) was nominated for the You-Can Buzzword of the Year Award. The word, which had been considered an otaku term, came to be used in everyday conversation, leading to the easing of the “otaku allergy” among the public.

How is it today?

A societal shift has taken place where people no longer feel the need to hide their interests, regardless of the genre. Even those who were considered high achievers in class can now openly identify themselves as “otaku.”

In 2019, Comiket saw its highest attendance ever, with 730,000 visitors over four days. This reflects the growing number of individuals who can now proudly claim the title of otaku, drastically different from when Nakamori wrote about the Comiket he attended in the 1980s. Today, otaku isn’t limited to just anime and manga enthusiasts. The scope of otaku culture has expanded significantly. Shin-Okubo attracts Korean drama and Korean idol otaku, while places in Ginza and Shinjuku cater to cosmetics and beauty enthusiasts.

At Comiket, company booths were set up in the Blue Sea Exhibition Hall in December 2019

A survey conducted between April and May 2020 by the youth marketing research institute SHIBUYA109 lab (surveying 8201 women aged 15-24) revealed that 67% of respondents identified with being some form of otaku such as “K-pop-ota” (K-POPヲタ) or “Band-ota” (バンドヲタ) or even “theme park- ota” (テーマパークヲタ).

It’s clear that otaku culture has gained widespread acceptance, particularly among the younger generation. Due to the broadening of its use, the term has become quite diluted and fallen somewhat out of common use. Although the image still doesn’t necessarily carry a cool “ikemen” or attractive image, the image of otaku has become much more nuanced, with people openly embracing anime, manga, idol culture, and online media as commonplace interests rather than niche, nerdy pursuits.

Who are the otaku’s abroad?

Of course, with the globalization of Japanese pop culture media, there are fans worldwide. And with widespread fandom comes widespread super fans. While the official definition in Japanese for otaku falls along the lines of a young person with a strong obsession with particular aspects of popular culture to the detriment of their social skills, the idea changes a bit when exporting to foreign cultures.

The term has become somewhat blended into a different subcultural term, “weebaboo” or “weeb,” which is used for someone who likes anime.

The origin of “weeaboo” can be traced back to the comic strip “The Perry Bible Fellowship.” At first, it held no particular meaning, but in 2005, it acquired significance through the 4chan (a platform inspired by the Japanese forums “ni-chan” and “2-chan” mentioned earlier) filter and rapidly spread across the internet.

Interestingly, the roots of this concept can be found in the late 18th and early 19th centuries when it was referred to as “Japonophilia.” This term describes a deep affection for Japan’s history, culture, and people. Individuals who were not part of Japanese society but exhibited a strong affinity for all things Japanese were called “Japonophiles.”

Two noteworthy early Japonophiles were Carl Peter Thunberg and Philipp Franz von Siebold, who played pivotal roles in introducing Japanese fauna, flora, and arts to Europe. Some British authors hailed Japan as a “rising star of enlightenment and human mastery.” This fascination partly stemmed from the waning British industrial supremacy and Japan’s rapid growth during that period. However, this enthusiasm waned during World War II.

As the 2000s progressed, the concept evolved into a different form. Negative terms emerged to criticize this obsession with Japanese culture. In 2002, the term “wapanese” emerged by combining “white” or “wannabe” and “Japanese.” It referred to individuals so infatuated with Japanese culture that they aspired to be Japanese themselves.

This expression gained popularity when 4chan users consistently targeted a small group of Japanophiles. In response to the controversy, site administrators replaced these mentions with the humorous slang “weeaboo.” Nevertheless, they used it untimely, allowing it to acquire meaning. The term “wapanese” fell out of favor because the brief period during which this filter was disabled was enough for the previously meaningless word “weeaboo” to gain traction and replace “wapanese” in mainstream culture.

In today’s context, “weeaboo” remains a derogatory term used to describe individuals deeply obsessed with Japanese culture, particularly anime, often elevating it above all other cultures. In many circles, “weeaboo” is criticized for its excessive and fetishized consumption of Japanese culture, which can perpetuate harmful stereotypes about Japanese people, treating them as fictional objects.

Understanding how this extreme fetishization can contribute to detrimental stereotypes, particularly those portraying Japanese women as exotic and submissive, sheds light on the criticism’s validity. This, in turn, can contribute to the alarming increase in rates of sexual violence against Japanese women in western cultures.

Alternatively, the abbreviation “weeb” attempts to distinguish ordinary anime fans who enjoy Japanese media from the more extreme cases of “weeaboos.” However, because of the strong negative associations surrounding the concept of “weeaboo,” it’s challenging to prevent this negative influence from spilling over into the related term “weeb.”

Consequently, adopting the term “otaku” has gained traction among those within the subcultural context. This version of “otaku” sidesteps some of the more negative stereotypes associated with it in Japan and instead aligns more closely with the idea of an “anime geek” – someone who enjoys anime to a significant degree.

Note: I would like to add a thank you to Matt Alt for his help in the research for this article. I highly recommend his book Pure Invention: How Japan Made the Modern World if you found the topic of this article interesting.

Links:

SHIBUYA109 lab. × CCCマーケティング共同調査第3弾! around20女子の”ヲタ活”生態比較 – https://www.ccc.co.jp/news/2020/20200623_001892.html

『オタク学入門』Toshio Okada https://web.archive.org/web/20001216171500/http://www.netcity.or.jp/OTAKU/okada/library/books/otakugaku/No1.html

『おたく』の研究(1)街には『おたく』がいっぱい中森明夫(1983年6月号)http://www.burikko.net/people/otaku01.html

→ English translation: Otaku Research #1 “This City is Full of Otaku” by Nakamori Akio (Translated with permission by Matt Alt) https://neojaponisme.com/2008/04/02/what-kind-of-otaku-are-you/

『おたく』の研究(2)『おたく』も人並みに恋をする?中森明夫(1983年7月号)http://www.burikko.net/people/otaku02.html

→ English translation: Otaku Research #2 “Can Otaku Love Like Normal People?” by Nakamori Akio (Translated with permission by Matt Alt) https://neojaponisme.com/2008/04/07/can-otaku-love-like-normal-people/