Likely when you think of Japanese history, you think of samurai and ninjas. However, while samurai were a prominent social class in feudal Japan, they comprise only one part of Japanese history. Before the samurai’s rise to power in the Heian Era (794-1185), there was an interesting and mysterious age known as the Kofun period.

So, what are kofuns? Kofun refers to large burial mounds found in Japan. These mounds are distinct archaeological features that date back to the Kofun period, which spanned from the 3rd to the 7th century CE. The term “kofun” translates to “old mounds” in Japanese.

However, what makes them interesting is that they weren’t just random mounds but were constructed with a unique keyhole shape. Inside were elaborate burial chambers made of wood or stone that held influential figures with all kinds of valuables, like bronze mirrors, weapons, armor, clay vessels, and jewelry.

Kofun sites are like time capsules, offering us juicy clues about Japan’s early political and social scene. It’s like stepping into a history book!

Sakitama Kofun Park in Saitama Prefecture

The Kofun Period (古墳時代 - 300 to 538 CE)

To start, a good question is: What is the Kofun period?

Kofun period dates from around 300 to 538 CE (just before Buddhism was introduced to Japan). Before the Kofun period was the Asuka period, which, combined, is referred to as the Yamato period.

Much of Japanese influence came from immigration from China across the Korean Peninsula, causing a common shared culture across southern Korea, Kyushu, and Honshu. At the time, Japan was made up of various ruling classes during the period of unification as various small communities became one big country under the rule of influential families. When the country was unified, it was originally named Yamato (hence the name Yamato period) before being renamed later to Nihon (日本) based on the belief of the emperor was a descendant of the sun god.

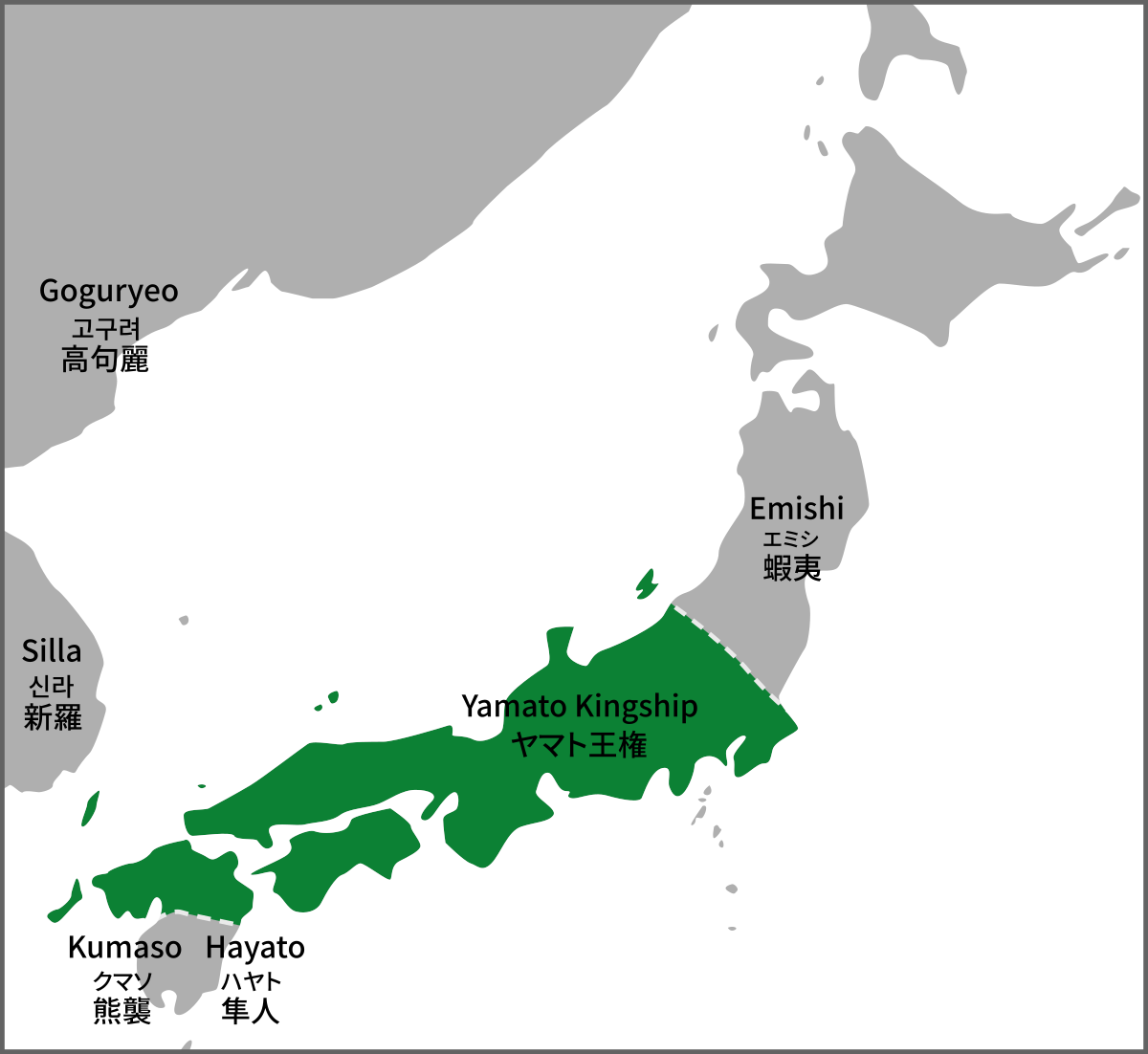

Map of Yamato from the 4th century to the 7th century

The Yamato court ruled with autonomy placed in local powers throughout the area. This ranged from Kibi (modern-day Okayama), Izumo (modern-day Shimane), Koshi (modern-day Fukui and Niigata), Kenu (northern Kanto), Chikushi (northern Kyushu), and Hi (central Kyushu) as the powerful clans distinguished Yamato politics.

However, throughout this time, Shintoism was the predominate religion with major noble families such as the Fujiwara family, who founded grand shrines. Due to the influence of Confucian cultures that immigrated to Japan, the social classes became pronounced, leading to a period of highly sophisticated funerary systems.

How are Kofun’s designed?

When it comes to Japanese kofuns, one cannot help but be captivated by their unique and striking shapes. These burial mounds display various forms, each with its own symbolic significance.

The most prevalent and recognizable shape among kofuns is the keyhole design. This design resembles, quite literally, a keyhole when viewed from above. The keyhole-shaped kofuns consist of a circular or rectangular portion at one end and a long, narrow, and elevated section that tapers towards the other end.

Daisen-Kofun, the tomb of Emperor Nintoku in Osaka

These kofuns are known as the “zenpo koen fun.” The square part of the keyhole shape (zenpo-bu) serves as the head section. In contrast, the entombed person occupies the round part (koen-bu).

The hori (or moat) is an evacuated area of earth used to make the mound forming a moat. In the case of zenpo-koen-fun, tsukuridashi is the area between the front and rear sections. Although for the en-pun (round kofun) or ho-fun (square kofun), tsukuridashi is the square portion attached to the main body. This space was commonly used for placing various items, including house- and equipment-shaped haniwa, tableware, and clay pots.

The grandeur and size of keyhole-shaped kofuns can be awe-inspiring. Among them, we find some truly colossal examples, such as the renowned Daisen Kofun in Osaka, extending over 400 meters (1,300 feet). These colossal monuments stand as testaments to the power and prestige of the individuals they were built to honor.

What kind of things are found in Kofuns?

Throughout the years, kofuns have been the center of archaeological discoveries allowing researchers to understand the ancient world of Japan better.

Among the most iconic and abundant discoveries from kofun sites is the haniwa, terracotta clay figurines. These figures represent a wide range of subjects, including warriors, animals, houses, and daily life scenes. Haniwa provides valuable insights into the Kofun period’s material culture, social structure, and funerary practices.

A Warrior Haniwa from the Kofun period

Kofun burials were also rich in grave goods such as bronze mirrors, weapons like swords and armor, jewelry, horse trappings, ceramics, and other luxury items. The exquisite craftsmanship and variety of these artifacts demonstrate the wealth and status of the buried individuals.

One distinct type of artwork commonly found in kofuns is magatama, comma-shaped beads made from various materials such as jade, agate, and other precious stones. Throughout historical texts such as the Nihon Shoki, magatama had a variety of references, such as the story of Susanoo, God of the sea and storms, receiving five hundred magatama from Tamanoya-no-Mikoto, the jewel-making deity. These items held significant religious and cultural importance during the Kofun period and were often found as grave goods.

A necklace of green jasper tube beads and chalcedony magatama

Sue ware pottery, known for its distinctive grayish-green color, was commonly used in the Kofun period. These pottery pieces were crafted precisely and often featured intricate designs and patterns. Interestingly, they were believed to have been first developed in the 5th or 6th century in southern Korea in the Kaya region. When immigrants migrated to Japan, they carried the style with them as it became a distinct style in contrast to native Japanese Haji pottery, which was more porous and reddish in color. It then became quite popular throughout southern Osaka and parts of eastern Honshu. The style was even used for roof tiles erected later in the Nara period.

Can I visit a kofun?

Visiting Japanese kofun sites is a fantastic way to immerse yourself in Japan’s rich history and ancient culture. Many kofun sites are open to the public, allowing visitors to explore these remarkable archaeological landmarks. While kofun’s are found all throughout Japan, Osaka and Nara are perhaps two of the most famous locations for kofun visiting due to their cultural importance within ancient Japanese society.

Some kofun sites offer guided tours or provide audio guides with detailed information about the site’s history and architecture. Check if these options are available and consider taking advantage of them to enhance your visit and gain a deeper understanding of the kofun’s importance.

When visiting kofun sites, it’s essential to observe respectful behavior. Follow any instructions or guidelines provided by the site management. Respect the area’s sanctity by refraining from touching or damaging structures or artifacts. Keep in mind that kofun sites are ancient burial grounds, so maintain a respectful and quiet demeanor during your visit.

Kofun sites you can visit!

Mozu Daisenryo Kofun: Located in Sakai City in Southern Osaka, around ten minutes’ walk from JR Mozu station or 20 minutes’ walk from the Nanai line at Mikunigaoka. It is quite close to Namba making it quite easy to visit.

Konabe Kofun: Located in the northern part of Nara city, if you keep heading north of Hokkeji you can come across two kofuns known as Uwanabe Kofun and Konabe Kofun. Located in the same area is also the grave of Emperor Heijo.

Sakitama Kofun Park: For those who don’t plan to visit Kansai, you can also visit kofun in the Kanto area. In Sakitama, Gyoda-shi, Saitama-ken, there is a park with various kofun you can visit. You can reach it by taking a train to JR Gyoda Station on the Shonan-Shinjuku Line. From there, you can take the Kanko Kyoten Junkan Course bus to the Sakitama Kofun Koen Mae stop.