One weekend, I decided to head to the office. With an important deadline looming and no plans for that Saturday, it seemed like a prime opportunity to get ahead on some work. To my surprise, upon entering the office, I wasn’t alone.

In America, the idea of voluntarily spending a Saturday at work may seem unusual, yet I soon realized it was common to see colleagues staying late into the night, sometimes until 10:00 or 11:00 p.m., even on weekends. Occasionally, I’ve even had peers who had pulled all-nighters at their desks.

It wasn’t long before I noticed that many of my friends also dedicated their Saturdays to work, with a six-day workweek being common for many people I knew. This is not limited to just my salary man friends, but also friends from all fields, hairdressers, real estate agents, carpenters, and so on.

The drive to contribute to one’s institution, whether a company or a university, is intense. On top of that, it’s also common to extend work-related interactions into social activities, such as drinking parties known as “nomikai“.

Although much has been written about Japan’s work culture, this article aims to explore its cultural underpinnings and the impact on mental health that this work ethic entails.

The drive to contribute to one’s institution, whether a company or a university, is intense.

How Many Hours Do Japanese Employees Work?

Historically, Japan was known for its rigorous work culture, often characterized by extended hours and minimal rights for workers. However, contemporary Japan has witnessed change, aligning more closely with global standards, where work hours and employee rights are protected by law thanks to reforms and shifting societal norms.

The prevalence of long work hours and the associated challenges, such as mental health issues and reduced work-life balance, have prompted governmental and organizational efforts to reform work practices. Initiatives aimed at limiting overtime and encouraging more equitable work schedules reflect a growing acknowledgment of the need for a healthier work environment. However, the persistence of traditional expectations and the slow pace of cultural change underscore the complexity of shifting work norms in Japan.

Statistical data indicates a notable reduction in annual work hours from 2,121 in 1980 to 1,903 in 2022, showcasing a significant decrease in working hours, surpassing even the reduction rate in the United States during the same period. This shift reflects broader changes within the Japanese workforce, including the rise of part-time and contract employment, contributing to the overall reduction in work hours.

Despite these improvements, the issue of overtime remains prevalent, particularly in traditional corporate environments where extended work hours are still viewed as a sign of dedication. The nuanced reality behind the statistics reveals that many full-time employees continue to engage in overtime work, influenced by workplace expectations and cultural norms that prioritize long hours as a demonstration of commitment.

The legal framework in Japan supports a standard 40-hour workweek, with any excess classified as overtime, warranting additional compensation. Various systems, such as predetermined overtime arrangements, provide flexibility in managing overtime compensation. However, these systems, while legal, may obscure the true extent of overtime work, as they include a set number of overtime hours within the standard salary package, only offering additional pay beyond these predetermined hours.

Where Does Japanese Work Culture Come From?

To understand Japanese work culture, it is important to understand both how Japan is similar to and how it is distinct from other East Asian cultures.

Like many Asian cultures, Japanese work culture is influenced by an emphasis on collectivism, where the needs and goals of the group are prioritized over individual desires. This is evident in Japanese organizations, where harmony (和/wa) and collective responsibility are fundamental principles guiding workplace interactions and decision-making processes.

Respect for hierarchy is another cornerstone of Japanese work culture, deeply rooted in Confucian values. This respect for authority shapes organizational structures and communication patterns within companies, where deference to seniority and adherence to established protocols are crucial. This hierarchical nature also supports a mentoring system, where senior employees guide and nurture the professional development of their juniors (also known as senpai/kouhai culture), further reinforcing the organization’s collective success.

Respect for hierarchy is another cornerstone of Japanese work culture

Furthermore, the concept of face (面目/menboku) and the fear of causing embarrassment to oneself or others play a significant role in the Japanese workplace. This influences not only the way feedback is given and received but also how decisions are made and communicated, often more indirectly than in Western practices.

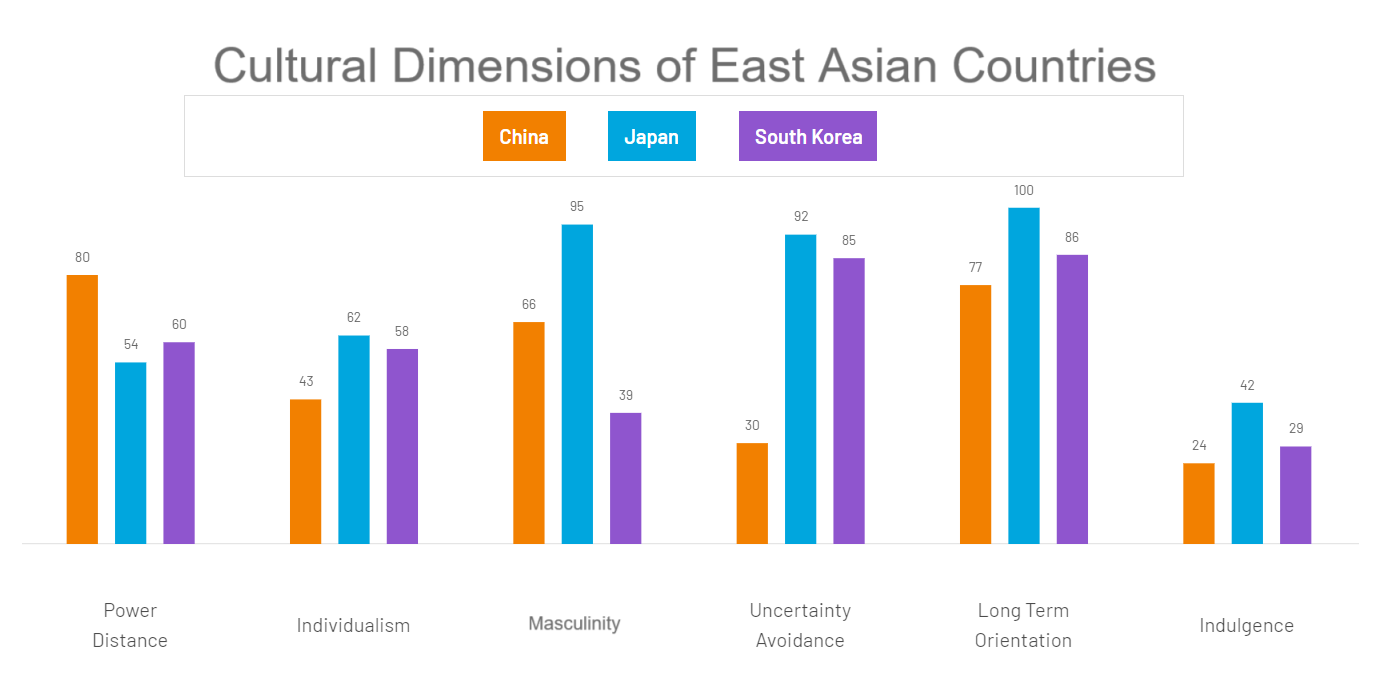

Because of this, long work hours can play a role in Japanese employees’ perception of work and life relationships, similar to other Asian countries. However, what makes Japanese culture distinct comes from its relatively high level of cultural masculinity. In Hofstede’s cultural dimensions, masculinity denotes competitiveness and ambition within society. This aspect in Japanese culture is greater than in other East Asian cultures like China and South Korea, resulting in pressure for perfection at work.

Based on the research found at Hofstede Insights

Along with this comes a strong loyalty and dedication to the company that is not merely a professional obligation but a deep-seated cultural value that influences employee behavior and attitudes. The notion of lifetime employment, although becoming less prevalent than in the past, is a testament to this, where employees would traditionally commit their entire careers to a single company in exchange for job security and corporate welfare. This also makes job mobility more challenging, as leaving a company can be a sign of disloyalty on your application.

What are the Mental Health Effects of Long Work Hours?

In the context of Japanese work culture, the mental health effects of prolonged work hours, night and weekend shifts, and insufficient rest periods have become a focal point of concern. The relationship between these work schedule characteristics and mental health is complex, influenced by various factors, including individual resilience to stress and the inherent demands of one’s job role.

The significance of this issue is underscored by empirical research suggesting a link between extended working hours and the deterioration of mental health among workers. For instance, long working hours have been associated with increased reports of mental distress among white-collar employees, even when accounting for individual differences that remain constant over time. The adverse mental health impacts are not limited to weekday overtime; weekend work, in particular, has been found to have a larger negative effect on mental well-being than additional hours worked on weekdays. This suggests that the loss of restorative weekend downtime, vital for psychological recovery and social engagement, plays a significant role in exacerbating mental health issues.

Moreover, the study highlights that while short rest periods between shifts do not directly correlate with mental health outcomes for white-collar workers, working post-midnight significantly affects the mental well-being of blue-collar workers. A statistic I have witnessed personally as I have had friends who have needed to take extra midnight shifts to make ends meet, only resulting in getting sick and being so fatigued on a day off they were unable to engage in any restorative or social activities besides sleeping.

How Does This Influence Foreign Workers in Japan?

Foreign workers in Japan may initially find the traditional aspects of Japanese work culture, such as the emphasis on group harmony, attending after-work drinking sessions, and the importance of non-verbal communication, difficult to adapt to. The concept of “reading the air” (understanding unspoken context and expectations) is vital but difficult when you don’t come from the same cultural background as those around you.

Foreign workers must navigate these traditional and modern elements, which can be daunting. Adapting to the Japanese work culture involves understanding and respecting its nuances, such as the hierarchical structure (see previous articles on Keigo for more information) and the value placed on harmony and collective effort. Engaging in social activities with colleagues, being punctual, and showing commitment through actions rather than just words are essential practices.

For better integration, foreign employees are encouraged to learn about Japan’s labor laws, including stipulations about overtime and paid leave, to understand their rights and obligations. Awareness of different work-hour systems, such as fixed, flex-time, and discretionary work systems, can also aid in adjusting expectations and work habits.

Faced with these cultural and structural dynamics, foreign workers in Japan can find opportunities for personal and professional growth. Embracing the positive aspects of the work culture, such as the emphasis on quality, teamwork, and respect, while also advocating for a healthy work-life balance can lead to a fulfilling experience in Japan’s evolving work environment.

Further Reading: