It’s no secret that the Yen is weak right now. I’m by no means an economist, so I won’t speculate on the reason why. Still, it’s a common notion that if you’re coming from another country to Japan (a task becoming easier as COVID winds down), then you may feel like you have all the money in the world once you hop off that plane and get your currency converted. Saving money may not be your priority going in, but it should be.

The reality, however, is that Japan—like any country—is constantly providing opportunities to spend a little more than necessary. I imagine some of you are hobbyists that would have your wallet gutted by a trip to Akihabara, Tokyo or Osu, Nagoya. Yet—also like any country—Japan is replete with opportunities to save money every day.

My parents taught me that you become broke from nickels and dimes, not dollars: A canned coffee here, a set meal there—small expenses add up, leaking away your cash without you even noticing. Everyone knows not to spend too much on frivolities, so I’m going to share some tips I’ve picked up on how to spend less on the most essential cost of all, food spending.

Skip the Vending Machine

It’s an oft-repeated (and true) point of trivia that Japan has a frankly absurd number of vending machines. On my block alone there are seven that are publicly accessible! At a glance, vending machines seem like a major convenience, and a fun one to boot: Forget your water bottle? Vending machine water. Feeling groggy on a hot summer afternoon? Vending machine coffee. Need something to warm you up while waiting for a train in the dead of winter? Vending machine cocoa.

So what’s the issue then? Well, gingerly put, vending machines are a rip-off. They’re designed to help you out when you’re in a pinch, as aforementioned, but they have a premium tacked on because of that. Even the superb 100 yen machines have prices that eclipse what you’ll find in a supermarket. For example, the cheapest canned coffee on my block is King brand—the one with the bramble-bearded sea dog emblazoned on the can. It’s 80 yen, which is much cheaper than other machine coffees like Boss or Georgia. Despite this, King is the exact same type of canned coffee sold at my local supermarket for 30 yen!

A difference of 50 yen may not seem like such a big deal, but if you’re like me and are addicted to coffee, then a can of King every day would come out to ¥18,250 (about $126USD) over the course of a year!

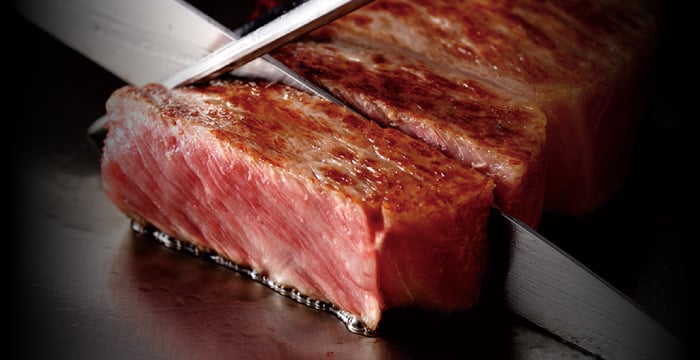

Don’t Buy Beef

Japan is a small, mountainous country with a dense population. Farmland is scarce compared to large countries like China and the USA. As you can imagine, this drives the price of beef to a premium. This is painful to accept if you’re American, Brazilian, or from any other country that loves beef. Yet, if your goal is to cut down on food spending, you’re going to have to stick to fish and chicken.

Oh, and speaking of Brazil: If you are going to buy beef for whatever reason, check to see if you have a Brazilian grocer near you. I’m not sure what arcane witchcraft they use to conjure beef of such good quality at such a low price, but they’re invaluable if you’re making a dish that absolutely needs cow meat. Even still, supermarket fish and chicken should be your default for saving money.

That tip isn’t so hard to adopt, but my next one is: When you buy meat, buy it frozen. Although I absolutely despise cooking with frozen meat, I regularly shave off thousands of yen from my monthly food costs by doing so. Japanese supermarkets will usually have some nondescript bag of frozen assorted seafood at a low price, and these are surprisingly versatile: I’ve used them in curries, stew, yakisoba, fried rice, etc. with little hassle.

If You Can, Buy Close to the Expiration Date

Just about every Japanese supermarket has a section devoted to vegetables on the verge of going bad or with blemishes. When buying vegetables, always check this section first. Japanese customers seems to have higher standards for their produce, and you can use this to your advantage. For example, a bag of apples containing one with a small brown spot can in some cases cut its price down to as much as half!

Japanese supermarkets are full of items marked 10-30% down for seemingly no reason. Well okay, the reason is because they’re likely a day old, but as far as I can tell, a 10% off package of kimchi tastes exactly the same as a full price one. Plus, food spending a day on the shelf never killed anyone. As mentioned before, these small differences in price do add up over time.

Sales can also depend on the time of day: Japanese supermarkets will start marking prices down around 9:00pm in the interest of selling out everything. Employees will begin making the rounds with a price gun around that time, and you’ll often even see customers orbiting around the bento section in order to snag their favorite as soon as its price is marked down.

Physically Check the Prices at Each Store

This is one where you’re going to have to do some investigation on your own. Find every single supermarket, farmer’s market and home grocer in your area and visit them all in person. Check the prices of the things you buy regularly and compare them to the other stores you’ve been to. You may be surprised, as I was, that the most intimidating stores often have the best prices.

Also, while I’m not sure how conducive this is to immersing into Japanese culture, getting a membership to Costco can be a great way to save on food spending. Because they’re a wholesaler, you can buy obscene quantities of essentials like meat and veggies at rock-bottom prices. That said, Costco does require a yearly fee in order to join, so if you can’t visit regularly then don’t bother unless you feel homesick for the U.S.

Cook at Home

This is the big one. If you regularly buy set meals, you’re wasting money. This may seem obvious, but it astounds me how many expats I see living off of this stuff. Granted, set meals in Japan are delicious, but the convenience of buying a portable, pre-made meal comes (just like those vending machine drinks) at a premium.

Think you don’t have the time? I’ve timed the microwaving of set meals against my own cooking, and on average I only save about 10 minutes when doing the former (granted, the dishes I made were on the simple side, e.g. curry, sandwiches). That difference is small enough that even the most busy among us should be able to set some time aside in order to do it.

That isn’t quite the long-and-short of it though. The bigger reason to cook your own meals is because you will immerse yourself in Japanese culture. Food has always been an excellent showcase of a culture’s likes, needs, history, and identity. It’s one thing to eat Ramen, but it’s another thing entirely to go through the painstaking process of making it from scratch. That process is part of learning about a different people: The methods and means of their very sustenance. With a keen eye at your local store and some elbow grease at the stove, you can not only start saving money but also become more acquainted with what it means to be Japanese.